Editor’s note: Second of two parts. Read part one by CLICKING HERE.

Editor’s note: Second of two parts. Read part one by CLICKING HERE.

A TANNING FAMILY AND A FAMILY THAT SOLD JEWELRY AND POSTCARDS are the current subjects of “Making a Living on First Street: F.J. Stumm and Ansley K. Salz,” an exhibit currently showing at the Benicia State Capitol Building. The Stumms, father and son, also are the subject of an exhibit now on display at the Benicia Historical Museum. In addition, Bookshop Benicia — the current occupant of the Stumm shop — is displaying a collection of historical images of the Stumm shop; and Dr. Jim Lessenger and Bob Kvasnicka recently recounted the Stumms’ history in the excellent article, “In Benicia, and Chronicling the West,” published in May by The Benicia Herald.

This is the story of the Salz family’s tannery that came to Benicia, grew into a huge industry in a complex of large buildings, then vanished completely, leaving not a trace.

* * *

ON JULY 13, 1880, LESS THAN A YEAR before his father became an owner of the Benicia Tannery, Ansley Kullman Salz was born. In 1900, while Ansley was a student at the University of California, his father died, leaving Ansley to take over his interest in the Benicia Tannery.

Though a young man, Ansley handled his new responsibilities well. In July 1907 he purchased a large Victorian mansion in Benicia on a bluff overlooking the Strait. He moved in with his younger brother Howard and Moses Salz, a cousin who was his same age. Both Howard and Moses had jobs in the Tannery. A picture of Salz’s house on the bluff, along with its neighbors, became a Stumm postcard and is included in the exhibit at the Benicia Capitol.

Not to be outdone by his young partner, that same year Herbert Kullman, who had become president of the tannery at his father Herman’s death, built a Colonial Revival-style house at the corner of East J and First streets for himself and his mother, Amalia. The Stumms created two postcards of this home, one of which is part of the exhibit at the Capitol.

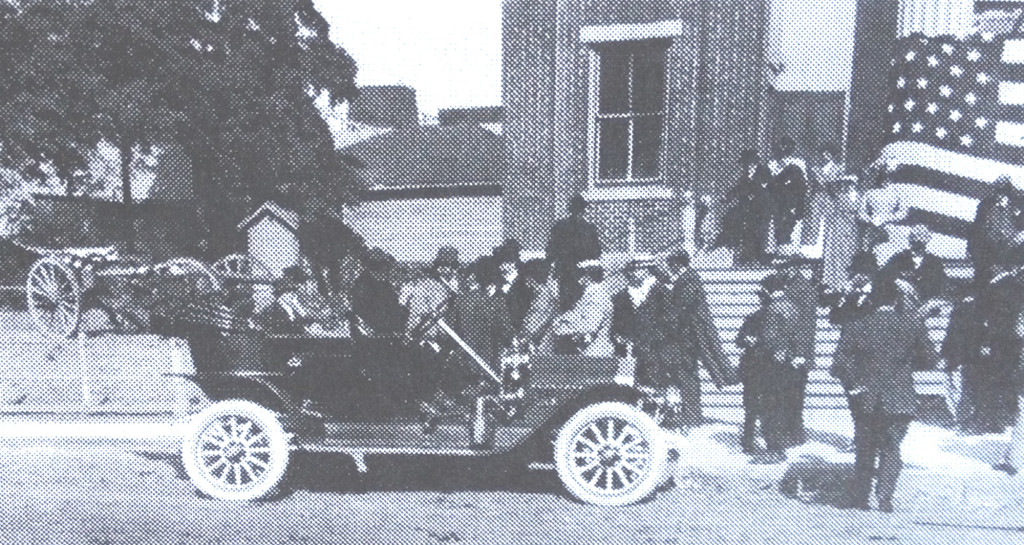

From photographs of Ansley in Benicia, it appears he enjoyed riding a horse around town. He also owned a beautiful, open, touring car — possibly the finest car in town. In 1910, Ansley used this car to transport a visiting politician who gave a speech at the old Capitol building.

Ansley also handled, smoothly, some family trauma. In late 1910, Herbert Kullman’s brother Jacob sought a divorce. Jacob’s wife believed he had a large financial interest in the Tannery, which she claimed should be considered in the divorce settlement. Jacob claimed he had no substantial ownership interest in the Tannery. To see what Jacob owned, his wife demanded that Ansley, secretary-treasurer of the Tannery at the time, allow her to see the Tannery’s financial books. Ansley refused. So Jacob’s wife sued to get access to the books — but a judge denied her request.

In June 1911, Herbert Kullman, age 39, followed in the tragic footsteps of his Uncle Moses. While living in the Hotel Sherman in Chicago, he shot himself in the head in his room. Herbert had been planning a trip to Europe, but he’d also been ill for several years, an illness that had recently included “nervous prostration.” In Ansley’s opinion, the only possible reason Kullman could have had for ending his life was brooding over his ill health. Kullman left an unsigned note that said: “Insane — cremate. Oh, mother, forgive.”The San Francisco Call reported that at the time of his death, Kullman was believed to be a millionaire.

After Herbert Kullman’s death, Ansley became president of Kullman, Salz and Co. At the time, he was only 29. He was not the type of person one would expect to be the president of a tannery company. He saw leather tanning as an art, not just a business. A concert-level violinist who later owned a Stradivarius violin, Ansley was close friends with Arsenal commander Colonel Benet’s son William Rose Benet (a later winner of the Pulitzer Prize for poetry) and William’s friend and house guest Sinclair Lewis (later the winner of America’s first Nobel Prize for literature). Later in his life, Ansley became good friends with Ansel Adams, the legendary nature photographer.

Ansley cared about his employees and was careful to photograph them, at all his tanneries, on a regular basis. A wonderful panoramic portrait, dated 1914, of Benicia Tannery workers standing on First Street in front of the Tannery is part of the exhibit at the Capitol Building.

In the fall of 1911, Ansley married a young woman from San Francisco, Helen Arnstien. Helen was a pianist, an artist — a painter of oils, pastels and watercolors —and a poet. Helen moved into Ansley’s Victorian mansion (while his brother and cousin moved out) and the two had their first child in Benicia.

As wonderful as the tanneries were for Benicia’s tax base and local employment levels, in the early 1900s factory work could be dangerous. In 1911, for example — the year of Herbert Kullman’s suicide and Ansley’s marriage — the Benicia Tannery garnered front-page coverage in the weekly Benicia Herald three times for accidents at the plant. In February, Joseph Martinez lost his right arm while working in the beam house; in March, Bernard Florence got caught by a freight elevator and was killed; and in July, Otto Meissner lost a hand in a rolling machine.

The Benicia Tannery closed, quietly, around the end of 1929. The Herald, at least, had no hint closure was coming. In July 1929 it reported that Moses Salz, after 28 years at the tannery, was leaving for the S.H. Frank Tannery in Redwood City, but the story made no mention of any coming closure. In late December, a small item on an interior page explained that in the process of liquidating, Kullman, Salz & Co. had been authorized to distribute $10,000 to holders of $100 stock and $1,306,080 of its capital assets. By this time, the Kullman, Salz Tannery in Santa Cruz had been sold to A.K. Salz Company (a company consisting of Ansley alone), and it was thought by The Herald reporter that the Benicia and San Francisco tanneries would be similarly sold.

But no one purchased the Benicia Tannery. The buildings remained abandoned at the end of First Street for almost 20 years, until the last of them was destroyed by fire by the end of the 1940s. A few years later the surviving smoke stack was removed. The last empty lots where the tannery once stood became the Olson Development of homes and shops early in the 21st century.

For more information, check out the exhibit “Making a Living On First Street: F.J. Stumm and Ansley K. Salz,” at the Benicia Capitol.

Donnell Rubay is a Benicia resident and the author of the Benicia-based novel, “Emma and the Oyster Pirate,” and “The Rogue and the Little Lady: The Romance of Anita Loos and Wilson Mizner.”

Excellent article. Thanks

Would be interesting to learn about the Crooks family and their banking and development activities somedau

Thanks for a good look at history. My father work in sales and went on to Santa Cruz to work for A.K Salzburg from 1929 to 1954.

Apple doesn’t deal with names well it is A. K. Salz .