Late artist left indelible mark on adopted hometown of Benicia

GUILLERMO WAGNER GRANIZO’S work will be celebrated with an exhibit at Benicia Historical Museum beginning Oct. 25.

Photos and images courtesy Benicia Historical Museum

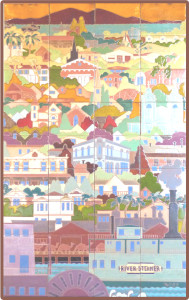

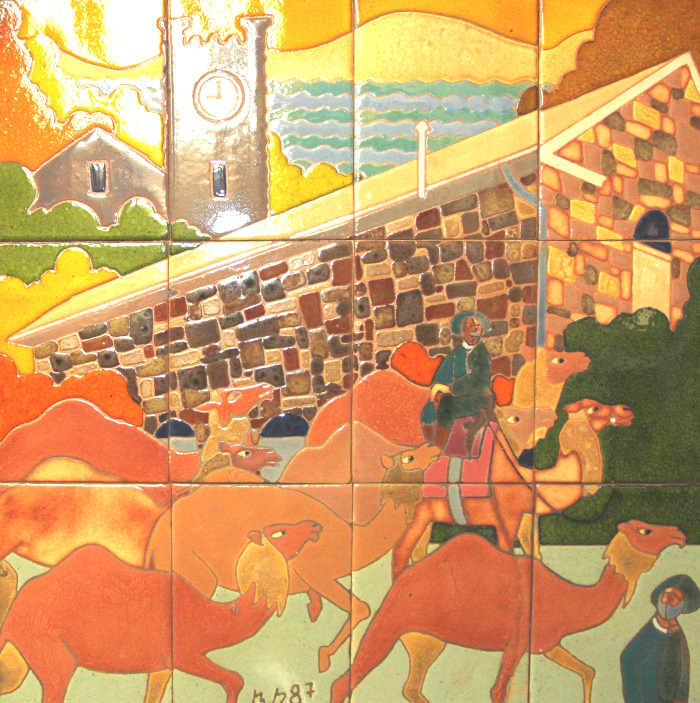

Granizo’s tile murals, mosaics, ceramics, tapestries and oils decorate homes and public spaces around the world. They also adorn the sidewalks of Benicia’s First Street, marking a sort of trail of the city’s colorful history.

In his autobiography Granizo wrote of a synergism of historical events, artists, places he lived, people he knew, cultures he experienced and things that happened to him that came together in his works. In the way that the art of the Congo River basin influenced Pablo Picasso, the ceramics of Spanish Colonial Antigua, Guatemala and Mexico influenced Granizo’s works. Benicia, too, became a key stop on the artist’s fascinating journey.

* * *

GUILLERMO WAGNER GRANIZO STARTED LIFE AS WILLIAM JOSEPH WAGNER. He was born to Joseph and Dora Wagner in San Francisco in 1923. His father came from the East Coast of the United States; his mother, from Nicaragua. Joseph never was able to settle on a stable occupation and was always chasing pots of gold.

When Wagner was very young the family migrated to Nicaragua to be with Dora’s family. The children — Dorita, Bill and Jerry — traveled with their parents throughout that country before moving to Guatemala and settling for a short time in Guatemala City. It was there that Wagner first started making sketches of birds, fish and other creatures on scraps of paper. He also was exposed for the first time to Spanish Colonial architecture and the art of nearby Antigua. He was enrolled by his father in a German school and was soon speaking English at home, Spanish with his friends on the block and German in school — a situation which, he later wrote, caused him to have difficulty with learning.

Wagner’s father eventually moved the family to Mexico City, where he opened a typewriter repair shop. For a while Wagner worked in the shop, but mostly he roamed the city and was home schooled by his mother. Ron Wagner, Bill’s son, described his grandfather as a “professional grave robber.” To entertain tourists, Joseph would dig up ancient artifacts and salt them in various archaeological digs so that tourists could “discover” them.

Destitute and in debt from a failed expedition to find Montezuma’s gold, Bill’s father decamped the family back to the U.S., first settling in Long Beach and then returning to San Francisco. The family attended St. Dominic’s Church, and Bill attended St. Dominic’s Elementary School, where he excelled in art. Wagner matriculated at Commerce High School in San Francisco, where he concentrated on art. He graduated on the eve of World War II and met Amalia Mary Castillo, a girl from a prominent Guatemala family that owned beer and automobile factories. Bill and “Mollie” would marry after the war.

It was natural that Wagner would attend the San Francisco Academy of Arts. He was developing into an accomplished artist and the Academy was surely happy to accept a hometown boy. But after one year the money ran out.

Bill Wagner gained work as a ship fitter at the Risdon Shipyard. To his surprise, he found that the yard workers would spend the days hiding out to avoid work. The opposite in temperament, Wagner organized work crews and was soon working on the USS Sullivan, a destroyer. In 1943, he and his brother entered the Army on the same day. Bill would go east to Europe, Jerry to the Pacific.

Normandy

“He told me that he had just made it to the sand when he was hit,” Ron Wagner, Bill’s son, later said. “A group of medics were working their way down the beach and found him barely alive. They placed him on a stretcher, loaded him on a jeep and transported him to a hospital. He was read the last rites four times and for the next four years he received penicillin shots each day.”

Bill Wagner was in D Company, 357th Infantry Regiment, 90th Infantry Division. The 90th Infantry, nicknamed “Tough ‘Ombres,” was split, with Wagner’s battalion landing on Utah Beach behind the 4th Infantry Division on June 8 and the remainder committed to battle two days later. The landing craft were fired upon by 88mm artillery and several were hit. Artillery rained upon the beach as the heavily equipped men waded to shore, and Wagner was hit by shrapnel that took out a kidney and left him paralyzed in the left leg. He was taken to a field hospital erected on the beach and underwent surgery, then spent the next four years in Army hospitals in England and California. He was later treated at the Fort Miley VA hospital in San Francisco.

While in a rehabilitation hospital near Auburn, Bill and the rest of the patients were provided art therapy to keep them occupied. It was there that he began experimenting with several types of media: sketches, film, leatherwork, watercolors and oils.

Back to San Francisco

Discharged with a brace for his paralyzed left leg, Wagner returned to Mollie and San Francisco where he built a home on the GI Bill. Mollie continued as a concert pianist and Wagner attended art school again. Their first son, Ron, was born that year, and Bob soon followed.

Wagner wrote that he attended classes regularly and absorbed all he could of art school, but didn’t pay any attention to grades or tests. In the end, he learned enough to land a job as art director for KRON TV. He hired five assistants, classmates from art school, and helped convert the station to color broadcasting. In the process he learned business skills that would help him in the future. He also became an expert behind the camera, developing a color compatibility system that was used internationally in the early days of color broadcasts. Dubbed the “ChromaChron,” the system was purchased by RCA.

Wagner also started experimenting in various forms of art. He first observed tile fabrication in Mexico while filming documentaries, and tried his hand with a few single tile paintings. Dr. Earl Herald, director of the Steinhart Aquarium in San Francisco, part of the California Academy of Sciences, contacted him to do a project for the aquarium. While on family trips, Wagner and the boys would search for variously shaped, textured and colored stones to fit into the mosaics Wagner planned for the project. Altogether it took months of experimentation. The result was four stone murals and 12 floor plaques made of various domestic and imported stones.

Family responsibilities began to weigh heavily upon Wagner, and he became increasingly frustrated at not being able to do what he really wanted to do — paint. So often, on family outings Mollie would care for the children and Wagner would go off on his own to work.

The Presidio

Wagner became chief of radio and TV productions at KRON and made films that documented the various operations of the Army in an effort to improve the Army’s image. He also made training films and became a radio personality. And he moonlighted as a writer, writing scripts for children’s TV shows such as “Casper the Friendly Ghost,” “Captain Zero” and “Rags the Tiger.” His repertoire expanded to children’s music.In his autobiography, Wagner repeatedly wrote about the synchronicity of his San Francisco birth, Latin-American upbringing, American father and Guatemalan mother. He pointed out that the remains of Juan Bautista de Anza, the man who founded Wagner’s hometown of San Francisco, were found under the floor of a church in Arizpe, Sonora, Mexico; Wagner and de Anza were of the same height and both had had a partially paralyzed left leg. Wagner eventually led a film crew to document the discovery and later returned to Arizpe to help create a sarcophagus for de Anza. In coming years he would return to Central America and Mexico for extensive travel and research. While there, the artist Beniamino Bugano encouraged him to work on mosaic murals.

Going to work for Wells Fargo bank, Wagner was responsible for producing media that would educate the employees. Creativity was not in the job description. But in his spare time, he carved a stagecoach and other items out of clay and wrote poems — dozens of them. He was unhappy and eager to create his own style and brand of art. Mollie was comfortable in her way of life, but he wasn’t. The boys had grown and left the house and his parents were ill and needed a lot of help. In time he had decorated his entire house, inside and out, with broken tile mosaics.

Wagner was turning fifty. “Dad was a role model, a business man, and my mother was a very emotional woman,” Ron said. Mollie was not happy. It was time for a change. They divorced in the early 1970s.

Metamorphosis

Entering his new life as a full-time artist, Wagner adopted a new name. “Nobody is going to buy art from Bill Wagner,” he told Ron. So he adopted “Guillermo,” Spanish for “Bill,” and “Granizo,” his mother’s maiden name. Ron suggested he keep Wagner as the middle name for continuity.

For the first time since returning after the war, Granizo moved out of San Francisco to Ben Lomond, in the forested mountains of Santa Cruz County. He lived with the artist Lark Lucas, who was originally from Salt Lake City. Through friends in the art world he associated with now-defunct Stonelight Tile Company of San Jose. It is there that he developed his art in tiles.

More transitions followed. After his parents’ deaths Granizo became connected with Mexican artists Jose Luis Cuevas and Francisco Zuniga. Later, he would place a tile mural in a Mexican museum dedicated to Cuevas.

The tile murals started coming in rapid succession. He did 17 for Washington School in San Jose and another at Mission Dolores. His gallery debut came at the Sun Gallery in Hayward; later he associated with Harcourts Gallery in San Francisco. He created the dramatic “Cathedral of Man” for the Institute for Scientific Information in Philadelphia, Pa.

While executing a mural for the Los Angeles Summer Olympics, Granizo moved to San Jose to be near the studio and tile factory. This led to a break with Lark, who was dealing with her own demons.

To Benicia

Granizo described his move to Benicia as a fluke. He moved into a home that had a four-car garage big enough for a studio. In Benicia, he met Toni, the last great love of his life. And of course he discovered a synchronicity with his life and his new hometown: Benicia had a Catholic church of the same name and architectural style as his home church of St. Dominic’s in San Francisco. It is also where Sister Dominica, the central figure of the ageless love story of Concha and Count Rezanov in Spanish California, is buried. Enchanted by the story, Granizo did several tiles featuring her.

Granizo described his move to Benicia as a fluke. He moved into a home that had a four-car garage big enough for a studio. In Benicia, he met Toni, the last great love of his life. And of course he discovered a synchronicity with his life and his new hometown: Benicia had a Catholic church of the same name and architectural style as his home church of St. Dominic’s in San Francisco. It is also where Sister Dominica, the central figure of the ageless love story of Concha and Count Rezanov in Spanish California, is buried. Enchanted by the story, Granizo did several tiles featuring her.

Describing his technique in an interview in Harcourts Quarterly, Granizo said, “I never use sketches, but rather create the painting on the tile as I work. I work with 12 tiles at a time, 3 across and 4 up, moving in a horizontal direction for continuity. It is impossible to visualize the completed painting in symmetry, color or form.”

He was prolific. He is said to have produced tiles and murals in rapid succession after obtaining a commission. He created works that decorate cityscapes in places as disparate as Lisbon, Fairbanks, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, Philadelphia and Salt Lake City.

The Benicia museum’s collection

When Benicia Historical Museum opened in 1985, Granizo introduced himself to then-curator Harry Wassmann with an offer of help. He soon embarked on a series of works portraying prominent early Benicians and important city structures. The results are on display at the museum. And he also executed a series of 30 historical plaques located along the city’s First Street. Guillermo Wagner Granizo died in Benicia in 1995, but not before leaving his indelible, and totally unique, mark on the city.

Learn ore about Guillermo Wagner Granizo at beniciahistoricalmuseum.org.

Dr. Jim Lessenger is a docent at the Benicia Historical Museum and the author of several books and articles on Benicia history.

Looking forward to this display & celebration!!