Historic medical and cultural journals credit the ancient Chinese with first recognizing the medicinal applications of the cannabis plant. Emperor Fu Hsi (circa 2900 B.C.) indicated that cannabis possessed the qualities of yin and yang, and was a very popular medicine.

Around 1450 B.C., a recipe for “holy anointing oil” is recorded in the Old Testament, using a plant called “kaneh-bosem,” believed by many scholars to have been a reference to cannabis. The recipe was olive oil infused with plant material. The ancients had effectively concocted a potent topical application for spiritual and medicinal uses. The ancient Egyptians (circa 1213 B.C.) record the first known use of cannabis as a treatment for glaucoma, still applicable today. Cannabis pollen is said to have been discovered on the mummy of Ramesses II.

Cannabis mixed with milk was used in 1000 B.C. India, in a drink called “bhang,” as an anesthetic. Other variations were used to treat illnesses much the same as the ancient Chinese did. At about 700 B.C., Persian religious texts indicate use of bhang and describe cannabis as the most important of thousands of medicinal plants. Around 600 B.C., Indian medicine proclaims cannabis to be a treatment for leprosy, indicating it to be a cure.

The Greeks recorded cannabis treatments in about 200 B.C., as did the Romans, who also noted the plant’s strong fibers for making rope (most likely hemp variety). Chinese medicine of 1 A.D. published recipes for using cannabis for over a hundred ailments. New Testament references to use of cannabis as an anointing oil are recorded at around 30 A.D. The Romans of about 70 A.D. published a medical journal identifying male and female species of cannabis.

Hundreds of centuries later, the record is consistent among Chinese, Greeks, Romans, Indians, Muslims, and others that cannabis had distinct medical applications, and could also induce a state of euphoria to calm anxious patients. William Shakespeare is said to have used cannabis extensively to stimulate his creativity in the early 1600s. Smoking pipes with cannabis residue are said to have been found at his estate. Cannabis (hemp) made its way to America with the Jamestown settlers in 1611. Hemp fiber was an important export, and those who did not grow it could be penalized.

In the mid-1700s to early 1800s, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson both grew cannabis on their estates as hemp for fiber. Napoleon is credited with bringing cannabis to France after invading Egypt, and it became widely accepted in Western medicine by the 1840s. By 1850, cannabis was listed in the United States Pharmacopeia as a treatment for a wide range of afflictions, including opiate addiction. Patent medicines of tincture of cannabis were sold to the public. By the 1900s, cannabis was used extensively in Eastern and Western medicine. In 1906, the Pure Food and Drug Act was enacted as the first consumer protection law, specifying product labeling of a variety of medicines, including those containing alcohol, opium and morphine. The sedative qualities of high doses of some strains of cannabis led to it being considered more as a possibly addictive and dangerous narcotic by the U.S. government. The introduction of powerful Middle Eastern hashish (pressed cannabis resin concentrate) into the U.S. furthered the belief that cannabis was a narcotic equal to opium, morphine, and heroin in producing sedation, euphoria, and “impure thoughts” (as an aphrodisiac). By 1927, 10 states had passed cannabis prohibition laws. The United Kingdom added cannabis to the Dangerous Drugs Act in 1928.

Beginning in the 1930s, early cannabis prohibitionists began to use the more exotic and pejorative word “marijuana” to describe cannabis and hemp, most likely inspired by the Spanish use of a similar name for the plants, “maria juana”, possibly an adaptation of the Portuguese slang word “mariguango” to describe an intoxicant. Consumer demand for cannabis-based medicines was on the rise. Pharmaceutical companies Parke-Davis and Eli Lily were selling extracts of cannabis for use as an analgesic, antispasmodic, and sedative. Another company sold cannabis cigarettes as a remedy for asthma. Research has shown that cannabis does in fact dilate bronchial passageways, even though the idea of smoking it is counter-intuitive in an asthma attack. Cannabis inhalers for asthmatics are available today.

Also in 1930, the U.S. government’s concern for rising use of narcotics during the Great Depression led to the formation of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, led by its first commissioner, Harry J. Anslinger. Anslinger maintained that all drug use was a “plot of civic corruption,” and that cannabis in particular caused insanity and would drive people to unspeakable criminal acts. The effort to demonize “marijuana” as a component of Mexican culture and by linking use to black jazz musicians in the US helped fuel Anslinger’s determined campaign against it. In 1933, newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst replaced the words “cannabis” and “hemp” with “marijuana” in his publications, often providing accounts of violent criminal acts allegedly fueled by “marijuana” use beforehand. Hearst is said to have financial interests in lumber and paper industries and was concerned about the competition from hemp.

By 1936, all 48 states had enacted laws to regulate cannabis medicines. The development of aspirin, morphine, and other opiates began to lessen the use of cannabis medicines. Some accounts indicate corporate interests in the development and sales of these drugs furthered the propaganda against cannabis. The legendary cult film “Reefer Madness” was distributed widely in the U.S. The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 caused a marked decline in physicians prescribing cannabis medicines because it was easier to not prescribe it than deal with the extra work specified in the new law. The Act was opposed by the American Medical Association, favoring more research in the substantial medical uses of cannabis, and denouncing the word “marijuana” as “a mongrel word that has crept into this country over the Mexican border.” By 1942, cannabis as medicine was removed from the U.S. Pharmacopeia.

The 1944 LaGuardia Report concluded “many claims about the dangers of marijuana are exaggerated or untrue”, and that it is not a “gateway” drug. In 1968, the U.S. government authorizes cultivation of cannabis for research on the campus of the University of Mississippi. That same year, the Wootton Report in the U.K. concluded that cannabis in moderate doses has no harmful effects, and that it is less dangerous than opiates, amphetamines, barbiturates, and alcohol.

In 1970, Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act to institute a “single system of control for both narcotic and psychotropic drugs.” Five drug schedule categories are established, and cannabis is placed in the most restrictive category, Schedule 1, reserved for drugs with “no currently accepted medical use.” Despite the bipartisan Shafer Commission report of 1972 concluding that personal use of cannabis should be decriminalized, President Richard Nixon rejected the recommendation, advocating instead for a “war on drugs.” As the ’70s came to a close, 11 states had decriminalized or reduced penalties for possession of cannabis.

In 1986, in response to a petition to reschedule cannabis to Schedule 2, Drug Enforcement Administrative Law Judge Francis Young opined that cannabis is “one of the safest therapeutically active substances known to man,” and recommended removal from Schedule 1. President Ronald Reagan rejected Judge Young’s advice.

Thirty one years later, despite thousands of years of recorded use of whole plant cannabis for medicine, it still remains, as far as the U.S. government is concerned, a plant with “no currently accepted medical use.” By contrast, 28 states and the District of Columbia now recognize the medical utility of the plant and regulate medical use. This year, bipartisan bill HR1227 was introduced to decriminalize cannabis altogether, remove it from the Schedule of Controlled Substances, and regulate it similar to alcohol and tobacco.

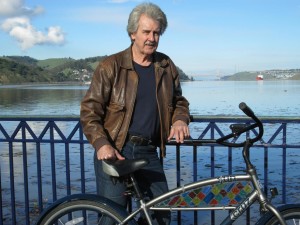

Stan Golovich is a 31-year Benicia resident, senior, veteran, artist, and cannabis advocate-educator. He is presently a Spring Semester student at Oaksterdam University in Oakland, America’s first “cannabis college.” He is the husband of former Benicia city councilmember Jan Cox-Golovich, and is often seen riding his bike on First Street, said to be the only bicycle in the world with a stained glass window in the frame, a product of his work in stained glass.

Leave a Reply