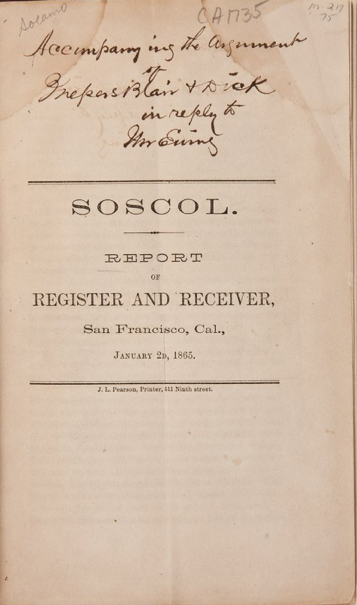

The arrival of Dr. Semple

Dr. Robert Baylor Semple was California’s first newspaper reporter, publisher and editor. His newspaper, The Californian, was the first newspaper published in California. He was a dentist who also had worked as an attorney, medical doctor, farmer and businessman before coming west on a wagon train in 1846. He was an exceptionally tall man — estimates vary from 6 feet, 8 inches to 7 feet in height — and somewhat of an eccentric, renowned for wearing fringed buckskins and a coon-skin cap turned backward so that the tail dangled in his face. During the winters he would wear a heavy buffalo robe coat over his buckskins.Semple participated in the Bear Flag Revolt of June 10, 1846, described as “an almost bloodless guerilla war with comic opera overtones.” The Revolt consisted of a group of Americans who left Sutter’s Fort, secretly entered Sonoma, captured Mariano Vallejo, manufactured a series of flags with bears on them, raised them, and then transported Vallejo back to Sutter’s Fort via the Peña Adobe that now sits just off Highway 80 between Fairfield and Vacaville.

Semple assumed the role of the adult of the raiding party, members of which later called themselves “Bear Flaggers,” and tempered the hotheads (the Bears) who wanted to shoot up the town and hang people. He and Vallejo became friends during the ordeal and Vallejo would later refer to Semple as “El Buen Oso” — the Good Bear. It was Semple who assisted the ailing Vallejo back to Sonoma once he was released by the Bears. By the time Vallejo returned to Sonoma, the Mexican War was over and California was part of the U.S., governed by a military governor.

There is a published story that the Bear Flaggers were sailing up the Carquinez Strait from Sonoma to Sacramento when Semple turned to Vallejo and pointed to what is now Benicia, saying something to the effect of, “That bay would make a good site for a town.” Considering the fact that the Bear Flaggers are known to have journeyed through what is now Vacaville, the story is undoubtedly false. More likely is that Semple was searching for business and land deals and saw the property on one of his later trips between San Francisco and Sacramento. He first approached the Martinez family with the idea of building a town on the south side of the Carquinez straits, but opposition from Captain John Walsh and Gen. John Frisbie, owners of the land to the east of Martinez, squashed the deal. Semple then approached Vallejo to buy the land that is now Benicia.

There is no record of what went on in the negotiations between these two hard-crusted businessmen but Vallejo sold the land to Semple for five hundred U.S. dollars in gold coin and a promise to name the town after his wife, Francesca. However, when the Alcalde of Yerba Buena received word that Semple planned to name his new town Francesca, he immediately changed the name of his small pueblo to San Francisco. Semple was left to name his new town Benicia, one of Vallejo’s wife’s other names. Afterward, Francesca Vallejo started referring to herself as Benicia and probably visited the town named after her when her daughter, Epifenia, was living with her husband, John Frisbie, in the house that is now across from City Hall.

The February 6, 1847 issue of the Californian contained the contents of the agreement between Vallejo and Semple:

“In the town of Sonoma, Upper California, on the twenty second day of the month of December, in the year eighteen hundred and forty six, Messrs. Mariano G. Vallejo, and Robert Semple, the first being the owner in fee of land known by the name of Soscol (sic), in the Jurisdiction of San Francisco, have agreed upon the following articles:

“1st. That between them, of their free will and accord, will found on the aforesaid land, a City, which shall be called, ‘Francisca,’ commencing the same as soon as possible.

“2nd. Said City to be built on the strait of Carquinez, within the Bay of San Francisco, commencing at a rock situated within said strait, and marked with the initials, ‘R.S. 1846,’ thence extending to the west five miles which shall be the present length of said City, and the breadth one mile from North to South.

“3d. The title to said land, being now held by Mr. Vallejo its legitimate possessor, he, by this agreement, grants to Mr. Semple in fee, and for his use, (en propriedad y uso fructo,) one undividable half of said five miles of land, with the condition that all of this said land (concession) shall be dedicated to the building of the said city Francisca.

“4th. As soon as circumstances may require it, there shall be established, at the cost, and on account of the contracting parties, a ferry, to facilitate the quick and easy communication between the two sides of the strait. Also, wharves to expedite the loading and unloading of the vessels which may trade there.

“5th. Semple, on his part, obliges himself to pay alone the costs of the survey and plan of the said place, and to direct personally said operation.

“6th. All the benefits, privileges and advantages which may result from the sale and leasing of lots, wharves, &c.&c, shall be divided equally between the two contracting parties, when and how they may judge convenient.

“7th. As soon as the population shall be prepared for the establishment of PUBLIC SCHOOLS, they will set apart for their use and the embellishment of the City, seventy-five per cent of the net products of the FERRIES and WHARVES.

“8th. Messrs. Vallejo and Semple reserve the right of adding to this contract such additional articles as they may deem necessary, which shall not be contradictory to the preceding.

“9th. For the sale or leasing of lots, or any contract, which shall refer to the building and advancement of the city and its population, it shall be necessary that the contracting parties concur, and that both sign such contracts.

“And that the preceding articles shall have due force, and fulfillment; the two contracting parties declare that they bind themselves and their successors, and their property in possession or to be possessed, and both sign before the Justice of the Peace of this jurisdiction, and the witnesses in attendance as the law requires.

M.G. VALLEJO R. SEMPLE

WITNESS. WITNESS.

VOR. PRUDON WM. M. SCOTT

“Done and executed in my presence this 23d day of December, 1846.

“[Signed,] JOHN H. NASH, J.P.

“Translated and recorded in the original, and translation on pages 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 & 32, of the land records of the District of San Francisco, Jan. 19th, 1847, by

WASHINGTON A. BARTLETT, Chief Magistrate of San Francisco

Californian, Feb. 6, 1847”

Robert Semple, land developer

As was and continues to be typical of land developers, Semple had no real money of his own, so he approached Thomas Larkin, the richest man in California at the time. Larkin, former United States counsel to Mexican California, had extensive land holdings and business connections. With Larkin’s money, in 1847 Semple ordered a survey of his future city to be done by Jasper O’Farrell, who also did the original survey of the city of San Francisco. Survey in hand, Semple got down to the business of selling lots. In addition to proposed streets and lots, the first survey included a “Military Reservation” to the east of the town.

A “Relinquishment Agreement” was executed so that Larkin could be included in the deal. It was reprinted in the July 10, 1847 edition of The Californian:

“In the town of Sonoma, Upper California, on the eighteenth day of the month of May, one thousand eight hundred and forty-seven, the following, by mutual and spontaneous consent was agreed to between Don Mariano G. Valejo (sic) and Robert Semple.

“1st. That making use of the right of retraction which belongs to them, it is their will to annul as they in fact do annul, the contract celebrated between the two on the twenty-second day of December, last year one thousand eight hundred and forty-six, by which the former ceded in favor of the latter the dominion and perpetual and hereditary usufruct (sic) of an indivisible half of five miles of land on the estate of Soscol (sic), in the Straits of Carquinez, with the object of founding in said land a city to be called Francisca, as the said contract expresses; which was celebrated in presence of Mr. J.H. Nash, at the time Alcalde of this jurisdiction, and is recorded in the Magistrate’s office of Sonoma, and likewise in that of the Yerba Buena, now San Francisco, at folios 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, and 32, in the month of January, of the present year, being then Magistrate of that jurisdiction Mr. Washington A. Bartlett.

“2nd. That whereas neither of the before-mentioned contracting parties have laid out any expense in the said place, nor sold any lots, nor granted any rights or privileges to any one; neither has any other person directly or indirectly gone to any expense in the said place, which to this day remains still in the same state as it was in, on the said twenty-second day of December, one thousand eight hundred and forty-six, both (of the contracting parties) by mutual consent, wish and agree that the said land, referred to in the contract of said date, return to the possession of Don Mariano G. Vallejo, its legitimate and sole owner, with the same rights and privileges which he had to and in it before said contract, which by these presents is declared to be null and void, by both contracting parties retracting spontaneously, freely, without compulsion, deceit, or fraud of any kind, the mutual obligations which they had contracted, and wishing to desist from and renounce, as they in fact do desist from and renounce in their own name and in that of their heirs, administrators or representatives &c., all and every one of the articles of the said contract, without exception.

“In certification and testimony of all which, they signed these presents, on the above date, in the presence of the Alcalde of this jurisdiction, Citizen L. W. Boggs and the undersigned witnesses.

M. G. VALEJO (sic)

R. SEMPLE

(Witness,) JACOB P. LEESE,

VOR. PRUDON.

“Territory of California, District of Sonoma

“Personally appeard (sic) before me the undersigned Alcalde of the District of Sonoma, Don Mariano G. Vallejo, and Robert Semple, all being personally known to me as the persons whose names are subscribed to the within instrument of writing, and acknowledged the same to be their act and deed, for the purposes therein-mentioned.

“Given under my hand and private seal at the office in Sonoma this 19th day of May, 1847.

(Signed,) LILBURN W. BOGGS

“The undersigned do hereby certify that the foregoing, as far as the signature of Vor. Prudon, is a correct translation, and the remainder a faithful copy of the original document.

W. E. P. HARTNELL,

“Government Translator. Californian, San Francisco, Saturday, July 10, 1847”

The “Deed for Benicia City,” from M.G. Vallejo to Semple and Larkin was executed on May 19, 1847. The Semple deeds were recorded on December 10, 1847, and the Larkin deeds recorded December 18, 1847.

There were no deeds from Larkin to Semple after Larkin withdrew from the Benicia land project and there was no land swap between Larkin and Semple for Larkin’s Colusa properties. After Semple’s death in 1854 the remaining Benicia properties that were in his name became the property of his wife, who in turn sold them.

Dreams of greatness die

In 1886 Hubert Howe Bancroft wrote these words to describe Benicia’s beginnings (edited for length and clarity):

“Vallejo’s chief motive was to increase the value of his remaining lands, by promoting the settlement of the northern frontier; and he was willing to dispose of his interest in the proposed town. The earliest original record that I have found is a letter of May 4, 1847, in which Semple writes of Larkin’s desire to buy the General’s (Vallejo’s) interest, and expresses his approval if the change suits Vallejo. Semple states he is closing up his business and will move his newspaper to Francisca by August at latest.

“Accordingly, on May 18th at Sonoma, Semple deeded back his half of the property to Vallejo. The next day, the 19th, Vallejo deeded his whole property, reserving the right to some town lots, to Semple and Larkin for a nominal consideration of $100.

“Semple transferred his newspaper in May, not to Francisca but to San Francisco and the Californian issues of May 29th and June 5th contained notices of the proposed town, sale of lots, establishment of a ferry, etc. Meanwhile Semple had gone in person to Francisca to start his ferry and have the town site surveyed by Jasper O’Farrell.

“Doubtless the city founders had counted on deriving an advantage from the resemblance of the name Francisca to San Francisco, against Yerba Buena, a name little known in the outside world. But the dwellers on the peninsula, as we have seen, had checkmated them by refusing in January to permit Yerba Buena to supplant officially the original name. Accordingly the speculators deemed it wise to yield; Semple writes on June 12th from ‘Benicia,’ and after a parting wail in the Californian of the 12th, the change to Benicia is announced in the issue of the 19th. In his letter of the 12th to Larkin, Semple says the plan is completed and the lots are numbered; several have been selected by men who propose to build. On June 29th articles of agreement were signed at San Francisco by Semple and Larkin. Lots of even number were to belong to Larkin and odd numbers to Semple; wharves and all privileges equally divided; each to sell or convey his interest without interference by the other; each donates 4 squares for public uses; each gives a lot for ferries, and 4 lots in 100 for town use. Semple returned at once to the strait; and in July Larkin contracted with H.A. Green of Sonoma for lumber, and with Samuel Brown to build 2 two-story wooden houses for $600 and 2 miles of land at the Cotate Rancho. The doctor was full of enthusiasm, was delighted at the success of vessels in reaching his port, and had no doubt that Benicia was to be the Pacific metropolis in spite of the lies told at the villages of S.F. and Sonoma. His great trouble was Larkin’s lukewarmness in the cause. It required the most persistent urging to induce L. even to visit the place late in the autumn. That a man in his senses should look out for a few dimes at Monterey and neglect interests worth millions of dollars at Benicia seemed to Semple incomprehensible. The doctor’s marriage that Christmas to Maj. Cooper’s daughter did not dampen his zeal. At the end of December, 28 citizens petitioned the governor for a new district to be set off from Sonoma under an Alcalde and on Jan. 3, 1848, the governor granted the petition, appointing Stephen Cooper Alcalde, and on the same day (!) consulting Alcalde Boggs at Sonoma as to the desirability of the proposed change. The boundaries of the Benicia District were: from mouth of Napa River up that stream to head of tide-water, east to top of ridge dividing Napa from Sacramento valleys, northwards along that ridge to northern boundary of Sonoma district, east to Sacramento River, and down that river and Suisun Bay to point of beginning. Early in 1848, E. H. Von Pfister began to act as Larkin’s agent.

“But in May came the gold fever to interrupt for a time Benicia’s progress toward greatness. On May 19th, Semple wrote that in three days not more than two men would be left; on the same day Von Pfister announced that in two months his trade had been only $50, and that he was going to the Sacramento, leaving Larkin’s business in charge of Cooper; and now H.A. Green came at last to work on long-delayed houses, actually completing one of them! Semple remained, for his ferry and transportation business became immensely profitable. The doctor promptly realized that the discovery of gold, notwithstanding its temporary effects, was to be the making of Benicia and a death-blow to its rival, San Francisco. All that was needed was to establish a wholesale house, obtain for ships the privilege of discharging their cargoes, if not of paying duties, at the strait, and induce one or two prominent shippers to make use of the privilege. Scores of traders came to Benicia from the mines, anxious to buy there and avoid the dangers and delays of a trip to San Francisco. If Larkin would only see his opportunity! But the Monterey capitalist was apathetic, blind to his opportunities as his partner thought. Exhortations, entreaties, and even threats seem to have had but little effect on him. Semple from July to December tried to make him understand that he was years behind the times, that he was by no means the ‘live go-ahead Yankee’ for whom Semple thought he had exchanged for Vallejo that he must wake up. On July 31st he threatened if Larkin did not come and go to work by Aug. 20th, to having nothing more to do with him. In December his indignation knew no bounds, when he learned that Larkin was thinking of erecting a row of buildings in Yerba Buena! This he declared the hardest blow yet aimed at Benicia, worse than all the lies that had been told, since it showed that the chief owner had no confidence in the new town. ‘For God’s sake, name a price at which you will sell out,’ he writes, and offered $25,000 for Larkin’s interest. Of actual progress in the last half of 1848 we have no definite information; but Bethuel Phelps finally became a partner with Semple and Larkin; and several years elapsed, as we shall see, before Benicia’s dreams of metropolitan greatness came to an end.”

The Military Reservation at Benicia comes to Rancho Suscol

U.S. armed forces entered California in 1845 with the Fremont Expedition. With the conclusion of the Mexican War in 1846, U.S. Navy and Army forces occupied the new territory and established bases of operation. One was the Presidio of San Francisco, a collection of mud brick buildings established by the Spanish and more or less ignored by the Mexicans. From the Presidio U.S. Army and Navy officials searched the San Francisco Bay area for appropriate locations for logistics and operations bases.

At the age of 23, Lt. James A. Hardie, a recent West Point graduate, was sent to California in 1846 to help organize the Army on the Pacific Coast. As a temporary major, he joined the Third Artillery Regiment, already in San Francisco. William T. Sherman was the junior first lieutenant. Hardie took command of all military and civil affairs in the state under the command of Colonel Mason. Sherman was his chief of staff.

Hardie and Sherman explored the West Coast for military installations. They selected the Presidio of San Francisco as their administrative headquarters and the Military Reservation at Benicia as the main logistical base for the West Coast and the Pacific. Sherman did the first survey of the reservation.

The city of San Francisco was thought to be inappropriate for a large Army site because of the high price of land and the vulnerability of the peninsula to invasion. The site at Benicia was decided upon as early as 1847 because of its free land from Semple and strategic location on the Carquinez Straits that linked the Bay to the California interior.

While cavalry and infantry units populated the land at “Benicia Point” as early as 1847, Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Silas E. Casey of the Second Infantry Regiment became the founder and first commanding officer of the Army outpost when he founded “the post at Point near Benicia” on April 30, 1849. At the same time the Benicia Quartermaster Depot was established and wooden quarters for both infantry and cavalry units were constructed.

From the beginning the cavalry post, quartermaster depot and arsenal were not a part of the city of Benicia. The land was purchased directly from Vallejo, Semple, Larkin and Phelps and appears as a “Military Reservation” on the first 1847 survey. During the 117 years they co-existed, the city never made an attempt to incorporate the Arsenal property into the city boundaries, an issue that would have to be resolved when the reservation finally closed.

The Benicia Arsenal was established between April 19 and April 25, 1851, by Brevet Captain Charles P. Stone. The infantry barracks, quartermaster depot and arsenal would share the same location but operate semi-independently until 1924, when they were united under one command by General John Pershing.

Lacking adequate funding and considering the poor quality of bricks in California at the time, Stone elected to use local sandstone quarried on the Arsenal grounds and redwood transported by ship from the Marin headlands to construct the Arsenal. Over the next nine years a guardhouse, two warehouses, a hospital, five magazines, a wharf and a fortress-like armory were constructed of locally quarried sandstone.

One of the reasons for the lack of funding from Washington, Captain Stone discovered, was concern on the part of the War Department that the title to the Arsenal property was not secure.

Title to the land of the military reservation was recorded in phases:

1. Deed from Robert Semple and wife and others (Larkin), dated April 16, 1849, and recorded July 5, 1949 in book C, pages 295-296, of records by L.W. Boggs, Alcade for Sonoma. Also recorded in Benicia, November 19, 1849, in book A, pages 460-461, of the records of Solano County.

2. Deed of release from Mariano G. Vallejo dated December 27, 1854, not recorded.

3. Dead of release from Thomas O. Larkin, dated December 30, 1854, and recorded January 24, 1855 in book I, page 347, of the deed records of Solano County.

4. Deed of release from Bethuel Phelps, dated January 20, 1855, and recorded January 20, 1855 in book H, pages 340-341 of the records of Solano County.

In addition, an act of the California Legislature approved on March 9, 1897 ceded the title to land below the high-water line to the Army to be used in trust as long as the Arsenal occupied the land.

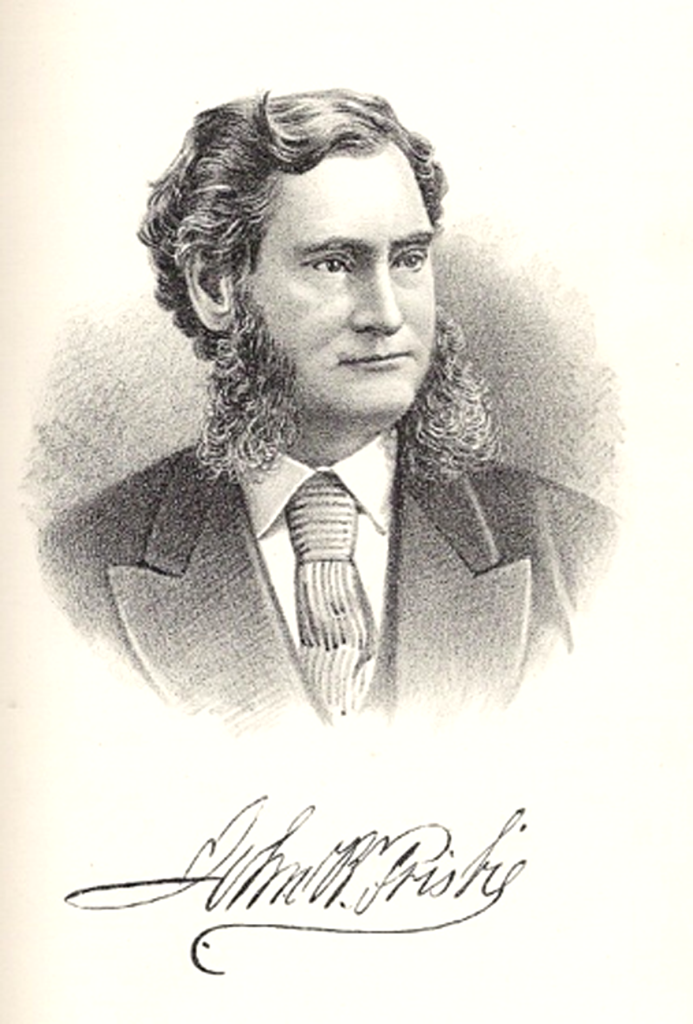

Enter John Frisbie

General John Frisbie was born in Albany, New York, on May 10, 1823. He and Leland Stanford studied law together with a prominent lawyer in Albany and subsequently Frisbie enjoyed a lucrative practice there. In 1846 he was elected captain of the Van Rensselaer Guard, a militia unit. During the Mexican War Frisbie recruited a company that joined the New York volunteers for duty in California. He arrived in San Francisco on March 5, 1847 and was given command of the Sonoma barracks in 1848; it was there that he met the Vallejo family. After his discharge Frisbie persuaded Mariano Vallejo to open stores in Sonoma, Napa and Benicia. While not a delegate, Frisbie took part as a legal consultant to the California constitutional convention of 1849 held in Monterey.In 1850 General Vallejo gave Frisbie power of attorney over Rancho Suscol. This allowed Frisbie to bargain, grant, and sell land on the Rancho and Frisbie did so by selling a large amount to capitalists in San Francisco. Frisbie and Vallejo created the new city of Vallejo with Frisbie doing all of the actual legal documents and sales in the project. On April 3, 1851 he married Epifania, the oldest and favorite daughter of General Vallejo and his secretary in later life. While Frisbie was occupied in numerous business dealings he coordinated the defense of his and Vallejo’s land titles involving several ranchos. Frisbie and other investors started the Vallejo Water Company and the Vallejo Land and Improvement Company which subdivided and developed the city of Vallejo into a modern city.

Vallejo proves his title to Rancho Suscol

Title to land was the key battle of 19th-century California. That and water. With the end of the Mexican War that had been deliberately provoked by President Polk to gain what would become the southwestern U.S., Mexico and the U.S. finalized the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. Part of the treaty was a clause recognizing legitimate land claims in the former Mexican lands.

Congress established a Land Commission to judge the legitimacy of each claim and Vallejo’s Rancho Suscol became case 318ND. Vallejo petitioned the commission in San Francisco by submitting certified and translated copies of the following documents:

1. A handwritten map.

2. A colonization grant to Vallejo dated March 15, 1843 signed by Governor Micheltorena and countersigned by Francisco Arce as secretary ad interim.

3. Another grant dated June 19, 1844, reciting that Vallejo had requested the purchase of the tract for the sum of five thousand dollars, that the governor had sold it to him for that sum and received payment, and declaring him to be the owner of the land without restriction. This paper also purported to be signed and countersigned by Micheltorena and Arce.

4. A certificate dated December 26, 1845 and signed by Pio Pico as governor and attested by Jose Maria Covarrubias setting forth that both grants mentioned above had been approved by the Departmental Assembly on September 26, 1845.

5. A letter dated March 16, 1843, addressed to Colonel D. Guadalupe Vallejo, military commandant of the line from Santa Juez to Sonoma and signed by Micheltorena and sealed with the seal of the Departmental Government. This letter purported to document that the Rancho Nacional Suscol was transferred from the Mexican Government to Vallejo in trade for goods and silver.

6. Letters and documents supporting the claim and documenting that Vallejo was using the land.

The Land Commission certified Vallejo’s claim as valid in 1855. It turned out to be just the beginning of the battle for Vallejo and Frisbie.

Death by litigation

People started coming in from the eastern U.S. looking for land to farm and ranch. Many started squatting on land owned by the Californios and the original settlers such as Frisbie, Semple and their investors. Squatters began settling on the rancho and Vallejo reacted by creating his own private army from the remnants of the Patwin and Miwok peoples and headed by the extremely tall Chief Solano. The resulting land war would rage for 20 years.

Both groups, the settlers and squatters in California, resented the vast sections of prime land that were locked up in huge ranchos like Suscol. After substantial lobbying on their part in Washington, the U.S. attorney for Northern California filed suit against Vallejo alleging that the title to Rancho Suscol was not legal. In 1856 and with Frisbie representing Vallejo, the case was tried before the United States District Court for Northern California in the city of San Francisco.

The U.S. argued that neither of the grants were referred to in Jimeno’s catalogue of Mexican land grants or recorded in the Toma de Razon, a Mexican record of governmental proceedings. No file was found on the grants in any Mexican government file. The journals of the Departmental Assembly showed that these grants were not before that body, either on September 26, 1845 as alleged in Pico’s letter, or on any other day.

Three witnesses on the part of the government testified that they knew the land, that it was called the Rancho Nacional Suscol and that it was occupied and cultivated by soldiers of the Mexican army down to the time of the American conquest. A Mr. Watson swore that in 1848 he proposed to purchase a part of the land from Vallejo and was told that Vallejo had bought it from the Suscol Indians but that he expected the U.S. government would swindle him out of it and refused for that reason to sell with a warranty of title.

Through his attorneys Vallejo produced witnesses supporting his position. J.B.R. Cooper testified that he was captain of the schooner California that transported goods from Vallejo in Petaluma to San Diego and that Governor Micheltorena told him that Vallejo had offered 20,000 silver Spanish dollars for Rancho Nacional Suscol and that the goods were to go in payment.

Four witnesses testified that Vallejo occupied and farmed Rancho Suscol for his own purposes after the purchase from the Mexican government. Vallejo produced a deposition of Pablo de la Guerra, a respected Santa Barbara don who declared that he knew the handwriting of Micheltorena and Arce and that their signatures on the two grants were genuine. Micheltorena had returned to Mexico after the American conquest but Arce was still in California and significantly was not called by Vallejo’s attorneys. Vallejo’s attorneys introduced a deposition of I.D. Marks who testified to conversations with Micheltorena in Mexico in which Micheltorena told him that he had extraordinary powers as governor and that his acts had been approved. Marks also testified that Jose Fernando Reyes, secretary of state of Mexico, said that the full powers to grant lands in California had been delegated to Governor Micheltorena by General Santa Anna under the “Bases of Tacubaya.”

Vallejo prevailed in the district court, having proved that the land purchase and land grant were legal under Mexican law and that he had taken all the necessary steps to make it legal under U.S. law.

To the Supreme Court

The U.S. Supreme Court saw it differently. In an 1861 decision the court said there was no official record of the transaction under Mexican law and therefore the grants and sale of land were not legally upheld by the Land Commission.

Justice Nelson wrote an eloquent dissent to the majority opinion:

“General Vallejo was one of the most distinguished men of the Mexican Republic; performed for many years the most important and valuable services, and was highly appreciated by the Supreme as well as the Departmental Government. He is now one of the most respectable citizens of California. His character makes it impossible to suppose that he would assert a claim to land which was not his own. In point of fact, no such suspicion as to this title ever entered the minds of Californians. They knew it was all right, and in that conviction large numbers of persons have bought these lands, thousands are interested in the confirmation, and there is no opposing interest which deserves the slightest favor.”

The Supreme Court decision resulted in the ownership of the former Rancho Nacional Suscol reverting to the United States Government. The action made thousands of land titles invalid, including that of the Arsenal.

Fallout from the Supreme Court decision

The Army took care of the Arsenal property immediately. The Arsenal land ownership was settled by a letter from President Abraham Lincoln:

Executive Mansion.

Washington City, October 7th, 1862

In conformity with the request of the Secretary of War of this date, it is hereby ordered that a plot of land at Benicia, in the State of California, described in a certain diagram now on file in the office of the Deputy Quartermaster General at San Francisco in the abovementioned State, be segregated from the public lands for the purpose of a Military Reservation; and the Secretary of the Interior is hereby directed to take such action as will secure the object and purpose herein set forth.

/s/ A. Lincoln

President of the United States

Hon. Caleb B. Smith

Secretary of the Interior.

Pre-emption

The land ownership of the persons who purchased portions of Rancho Suscol from Vallejo, Frisbie or Semple was in jeopardy. As news of the Supreme Court decision spread, more squatters came into Rancho Suscol, challenging the titles of the people who had already legally purchased property in the former rancho.

The land ownership of the persons who purchased portions of Rancho Suscol from Vallejo, Frisbie or Semple was in jeopardy. As news of the Supreme Court decision spread, more squatters came into Rancho Suscol, challenging the titles of the people who had already legally purchased property in the former rancho.

The issue of land ownership pre-emption was not new to Congress. The concept was that owners of land from a previous regime would pre-empt the title to the land over others coming into the area. Owners of land in former British, French and Spanish territories (and later, Russian and Hawaiian territories) were able to pre-empt their lands from use by other immigrants. The Native Americans were not so lucky.

Frisbie immediately took action through Timothy Phelps, California’s member of the House of Representatives, to introduce in 1862 a Pre-emption Act specific to California. The act would have guaranteed title to the settlers who already owned the land at the time of the Supreme Court decision, thus freezing out the squatters and ensuring the land titles of those settlers and investors who had purchased the land legally from Vallejo. The act failed because of concerns over acreage limits.

Land War: The settlers bring in the Regulators

In the year following after the Supreme Court decision, 189 squatters flowed onto the former rancho, erecting sheds, tearing down fencing and building homes. The response of Frisbie and Vallejo was to step up the campaign against the squatters. They brought in “Regulators,” hired guns to clear the land of squatters. Yes, Regulators. They were a lot more than a Hollywood fiction. Hardened men, many of them veterans or deserters from the Union and Confederate armies, they were heavily armed and conducted midnight raids, shootings and threats. Violence was a way of life for these thugs. People were murdered on both sides.

Frisbie also initiated and won several lawsuits to protect his rights to Suscol and other lands affected by the Supreme Court decision and squatter encroachments.

In 1863 Phelps introduced another pre-emption bill before Congress, this time with no limits on acreage. It passed, thus guaranteeing the titles of the settlers and investors on Rancho Suscol and other former ranchos and freezing out the squatters. The settlers celebrated with a giant barbecue at Suscol House, where more than 1,000 guests of Frisbie and his partners enjoyed steaks and copious amounts of alcohol.

The land war heated up. The investors and settlers hired more Regulators to terrorize the squatters into leaving the land. Many did; others accepted cash or land bribes to leave. The federal land commissioners also tried to charge landowners in the cities of Benicia and Vallejo more money to patent their lands than those in the rest of Solano County. Benicia City Council hired attorney Lansing Mizner, a relative of Robert Semple and father of famous architect Addison Mizner and playwright Wilson Mizner, to write a petition to Congress asking that landowners in the cities be charged the same low price as those in the countryside. It worked.

Over the next three decades the federal government wrote hundreds of patents (the federal term for deeds) for properties in the former Rancho Suscol and other ranchos in California. The patents were duly recorded in the Solano County Recorder’s office and can be viewed there today in seven leather-bound volumes. The last patent was issued, and the Rancho Suscol case finally closed, in 1893. The last land case from California arising out of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo was adjudicated by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1943.

Leave a Reply