320 killed when ammo ships exploded; disaster led to mutiny, reform

THIS IS THE STORY OF THE PORT CHICAGO EXPLOSION that occurred 70 years ago on July 17, 1944. You can see where it happened by going to the scenic overlook next to the Benicia-Martinez Bridge and looking southeast to the other side of the Carquinez Strait.

THIS IS THE STORY OF THE PORT CHICAGO EXPLOSION that occurred 70 years ago on July 17, 1944. You can see where it happened by going to the scenic overlook next to the Benicia-Martinez Bridge and looking southeast to the other side of the Carquinez Strait.

It was wartime and the mission of the Port Chicago Naval Weapons Depot was to take munitions directly from rail cars and load them onto Victory and Liberty ships to be shipped by convoy to the Pacific Theater of operations. The work was backbreaking and done by Black sailors in a racially segregated unit.

* * *

THE CRACKS IN THE GLASS of two stained-glass windows in the Community Congregational Church on West Second Street tell a story of profound tragedy.

The first is called the “Jesus Window.”

It had been well made when it was installed in the original sanctuary, the opalescent glass reminiscent of Tiffany. But there are problems. The lower panes are cracked and there is evidence of extensive repairs to the leads and solder joints. Some of the 19th-century panes have been replaced with more recent 20th-century glass. The cracks in the glass resemble “shock cracks” caused by a blast.

The second stained-glass window is in an alcove above the entry to the sanctuary. It also has shock cracks and the 19th-century work has been trimmed and surrounded by a collar of 20th-century work. It looks similar to blast-damaged glass in the cathedral in Vienna.

Both windows were transferred in the 1960s from the old sanctuary on West J Street to the new one on West Second.

‘A bad night all around’

The evening of July 17, 1944 was, by all accounts, warm. By 10 o’clock most Benicians had gone to bed. At the Yuba Manufacturing plant, the swing swift was winding up. On the floor of the main machine shop a crew of women were busy manufacturing howitzers. Suspended high above the floor in operational booths, teenage girls, some still in high school, ran huge cranes that moved the parts around. The girls had been hired to replace the men called to war.

On First Street, the State and Victory theaters were showing newsreels of the landings at Normandy. The Alamo, Union, Pastime and Washington House clubs were open for business and doing a good wartime trade. The Fernandez Pool Room was full of customers, as were the other clubs, pool halls, card rooms and bars — including some 15 houses in Benicia that employed about 50 “girls,” who were doing their part for the war effort.

At the Congregational Church on West J Street, the Rev. Elmo Wood was in a meeting in the sanctuary with four other men, but the subject of their conversation has been lost to history.

At 10:19 p.m. the windows of the east side of the church exploded inward, showering the men with razor-sharp shards of glass and causing multiple cuts on their faces, necks, arms and torsos. The flying glass was followed by the sound of an enormous explosion — or maybe the noise came first; people were unsure.

Across Benicia, sleeping residents were thrown out of bed and onto floors. Doors were ripped from their hinges and garage doors were blown open and down. The patrons and girls in the bars and clubs were struck by flying glass. The east windows of St. Dominic’s Catholic Church and the St. Catherine’s Seminary were blown in. The stained-glass window behind the altar at St. Paul’s Church shattered inward. On First Street, the windows on both sides of the street were turned into lacerating missiles, and the products on display thrown into the street.

In the Arsenal, workers on the swing shift were knocked to the ground or into walls by an enormous bone-breaking blast that also turned windows into thousands of blades. The power went out and, with it, the lights.

In the Arsenal, workers on the swing shift were knocked to the ground or into walls by an enormous bone-breaking blast that also turned windows into thousands of blades. The power went out and, with it, the lights.

Then, the survivors agreed, there was a stunned silence.

Everyone rushed out into the streets in their bare feet.

Immediately, the Red Cross, having prepared and trained for such an event, sprang into action. They opened the emergency hospital at St. Dominic’s Church that had been pre-positioned during the first year of the war in anticipation of an attack. Boy Scouts from Troop 7 donned their uniforms and campaign hats to help with the injured. Drs. A.C. Atwood and L.H. Sanborn operated through the night, suturing lacerations, removing glass and setting fractures. Most of the injuries were cuts to the feet of people who had run into the streets, but there were many eye lacerations and neck injuries where severed arteries demanded immediate surgery. It was, one citizen was quoted saying, “A bad night all around.”

Injured Benicians taken to Vallejo General Hospital found it choked with other injured residents: Vallejo had also sustained a lot of damage from the blast. More than 600 doctors, nurses and technicians from the Mare Island Naval Hospital came to Vallejo and Benicia that night to help civilians.

With the power out, the Spartan Brothers Circus, in town for a performance at the Arsenal, provided its generators to the Arsenal hospital and to the emergency hospital at St. Dominic’s. The entire Benicia Police Department responded and was later reinforced by military police from the Arsenal, Mare Island and Hamilton Air Field in Marin County.

The damage to Yuba was superficial. Broken glass littered the floors and machines and the power was out. The biggest problem was in extracting the terrified teenage women from the control cabs of the huge cranes. Too shocked to climb down the ladders, they had to be removed using hastily constructed scaffolding.

Sunrise reveals disaster’s extent

By the morning of July 18, the residents of Benicia knew that a terrible explosion had occurred at the Port Chicago Depot, 8 miles to the east, and that the Arsenal and city had taken the full brunt of the blast. Every east-facing window in Benicia was destroyed, and most of the others as well.

First Street was a mess. Every window had been blown out on both sides of the street. The windows of the State and Victory theaters, the City Meat Market, Belknap’s Clothing Store, and the Safeway were destroyed and military police were posted to prevent looting. The windows of City Hall (now the Benicia Capitol State Historic Park) were damaged and flying glass had shredded the books in the library and the furniture in the offices. Only the Pastime Club (now the Relik Tavern) and the Fernandez Pool Hall escaped damage — probably, someone suggested, because it had been a warm evening and the patrons left the windows open.

The windows of the Masonic Temple, Odd Fellows Hall and B.D.E.O Lodge were shattered. Many glass frames on the walls of the buildings were also smashed and some leather and felt furniture was shredded by flying glass.

At the Congregational Church, in addition to damage to the “Jesus Window,” four memorial windows were shattered that had been installed to celebrate five Benicia pioneers: Mr. and Mrs. George McKay, Harriet Wetmore Jones, Mary June Hunt Tarbox and Walter R. Johnson.

School was cancelled for the remainder of the week and everyone in town went about the business of cleaning up the mess. Throughout the day, Army and Navy personnel brought in tons of plywood for use as temporary window and door coverings. The military also sent hundreds of men to help with the cleanup.

School was cancelled for the remainder of the week and everyone in town went about the business of cleaning up the mess. Throughout the day, Army and Navy personnel brought in tons of plywood for use as temporary window and door coverings. The military also sent hundreds of men to help with the cleanup.

By that evening the theaters, bars and clubs had reopened and Yuba Manufacturing and the Arsenal were back to full production. There was a war on, after all, and no time to linger over disaster. The emergency hospital at St. Dominic’s Church remained open.

The Herald reports despite censorship

The Benicia Herald was published the morning of July 20 and contained the description of the blast and the consequences to the city. The amount of detail in the articles was surprising considering the level of wartime censorship present at the time.

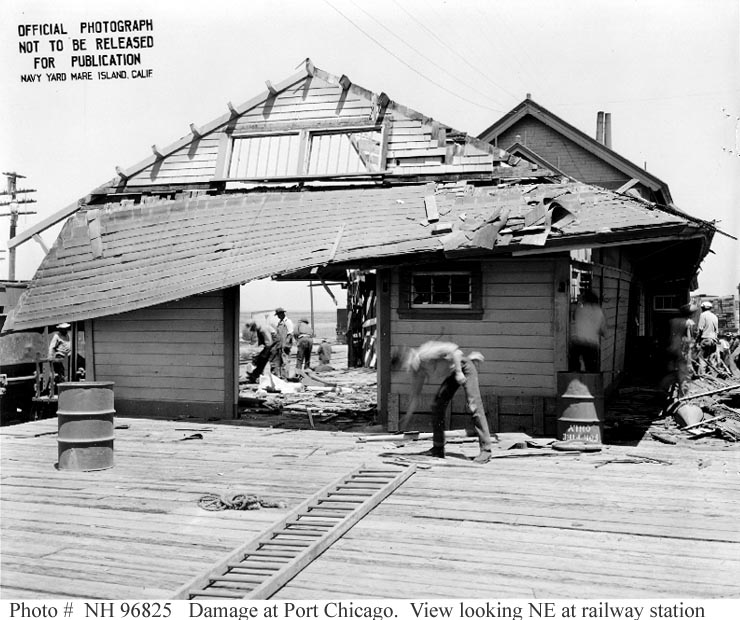

Benicians learned there had been a massive explosion at the Port Chicago Weapons Depot when the Victory Ship “E. A. Bryan” exploded while loaded with 10,000 tons of munitions. They learned that more than 300 persons were killed, and that the Yuba Manufacturing Company suffered $4,500 damage and the Arsenal $150,000. Thousands of citizens and military personnel had been injured, many seriously. The hospitals were still full.

The city of Port Chicago was destroyed, and Martinez took a more severe blow than Benicia. So bad was the damage to the Martinez hospital that ambulances from Oakland were called, and the Oakland and Berkeley hospitals were soon full of injured military personnel and civilians from Port Chicago, Martinez, Crockett, Concord and Walnut Creek. Concord and Walnut Creek had been nearly destroyed, as well.

Wartime censorship descended again. In subsequent editions all news of the explosion and damage was blacked out from The Herald — except for one article in the next edition that announced that citizens could request compensation from the Navy. An address was given.

The aftermath

At the Depot, 320 servicemen were killed and 390 wounded, including the crews of the ships in port. Unexploded ordnance was hurled in all directions, including across the strait toward Benicia.

A month later the surviving black servicemen, many suffering from what was later known to be traumatic brain injury from the blast, refused to load more ships and were convicted of mutiny. The Port Chicago mutiny would later be seen as another step toward racial desegregation of the Armed Services.

Recovery and legacy

Benicia recovered and went on with the business of supporting the war effort. The churches rebuilt their windows and the city repaired itself. Rev. Elmo Wood of the Congregational Church and others carried the scars of that night for the rest of their lives. In 1946 the church received a check for $164 to cover the costs of damage to the windows, but only two could be repaired. In the end, some of the cracks were deliberately left as a reminder of that night, but the explanations behind them were lost as the war generation died and subsequent generations built a new church and sold off the old one.

The two windows transferred to the new sanctuary remain a mute reminder of the need for preparation, a terrible disaster and a heroic city response.

Dr. Jim Lessenger is a docent at the Benicia Historical Museum and the author, most recently, of “Commanding Officer’s Quarters of the Benicia Arsenal.”

Leave a Reply