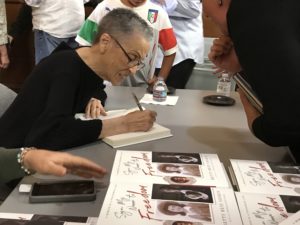

Betty Reid Soskin, a 97-year-old National Park Ranger, signs copies of her book “Sign My Name in Freedom” at the Shell Clubhouse in Martinez on Saturday. (Photo courtesy of Ken Mitchroney)

By Donna Beth Weilenman

Martinez News-Gazette

Although Betty Reid Soskin’s work in Richmond during World War II helped the Allied cause, she doesn’t consider herself a “Rosie,” even though other women who helped assemble Victory ships would welcome her into their fold.

She secured no rivets. She welded no metal seams. She built no war machines to combat the fascist enemies that threatened to take over the world.

Instead, she filed information cards that gave her a front row seat to racism of the day. Because of what she saw, she avoided subsequent White House honors for her service, and tried to suppress the feelings of anger at the injustice.

It would take an invitation by President Barack Obama, who gave her a presidential challenge coin, for her to realize her contribution.

She lost that coin during a home invasion, in which she battled, then escaped her attacker, barricading herself in her bathroom, then plugging in her iron so if the man broke in, she could brand him so police could identify him. Instead, he took what he pleased and left. Of all she lost, she regretted most that he took the presidential coin.

Once Obama heard of the robbery, he sent a replacement along with a personal letter.

Reid Soskin, who will be 97 this year, became a National Park Ranger just 12 years ago. She is the park service’s oldest ranger, and she has spoken up to tell the history she saw firsthand, influencing the Rosie the Riveter Museum in Richmond, where she works full time.

During her appearance Saturday in the Shell Clubhouse, she read from her newly released autobiography, “Sign My Name to Freedom.”

The book itself began as a blog that was spotted by a publishing house that convinced her it could become a book. While she worked with Editor J. Douglas Allen-Taylor, “each word is mine,” she said.

It describes how she was a clerk, working in an all-black union, filing cards on all the African-American Kaiser Shipyard workers, many of whom had been brought from other parts of the country, especially the South. Richmond’s population swelled to 100,000 and beyond from a mere 23,000 before the war started.

Many were among the people who built 747 ships in three years and eight months.

But alongside each of the African-American workers’ names on those cards was the word “trainee.” That meant they would never compete with white workers, and their accomplishments during the war effort would not transfer to post-war life, she explained.

That wasn’t the first time Reid Soskin had run into prejudice. Her family had moved to California from Louisiana, a place where her grandfather, a noted builder, had to leave by sundown, taking his family away from his home state for a year after he dared call a white man by his first name – the same way the white man addressed had done to him.

Eventually, the family moved to Berkeley. Once in the Bay Area, Reid Soskin never moved beyond Contra Costa and Alameda counties. But California was not always fair to all its residents, she observed.

She realized the pledge to the flag contained the words “with liberty and justice for all” that didn’t appear to apply to people of color. So she chose only to mouth the words but not say them, to honor her personal conviction without disrespecting her classmates or a teacher she admired.

Rather than the overwhelming patriotism others felt during World War II, Reid Soskin said it was a confusing time to her, creating “painfully mixed feelings.”

Because the United Service Organization (USO) didn’t entertain African-American military members, Reid Soskin and her then husband, Melvin Reid, who became known in the East Bay music scene, welcomed them to her home periodically, using lemonade parties to create their own de facto USO. She only knew a few of their names, and sometimes wonders if any were among the unknown lost in the Port Chicago explosion in 1944.

She described other aspects of the Kaiser Shipyard – it had hospital services that became the progenitor of the health maintenance organization (HMO) method of health care. It provided 24-hour child care and became the site of a community college.

After the war, the buildings associated with the African-American contributors to the war effort were torn down. Some people used leftover materials to build lean-tos. Kaiser Shipyards expected the large number of workers would return home, but that didn’t happen, she said.

Those stories fueled a rage in Reid Soskin, which she managed with civility, until she saw how Hurricane Katrina victims were treated.

“I needed that to stiffen my spine,” she told her Martinez audience. “I think my rage served me well.”

And she used that rage positively when she was invited to attend a 2003 planning session on the Rosie the Riveter museum that would tell the war story through the eyes of women.

“I learned how history becomes revisionist,” she said, because the park service often uses buildings to tell stories – and those associated with the African Americans had been demolished. There is no great conspiracy, she said. Instead, “What gets remembered is a function of who is in the room to do the remembering.”

She was there, not as a legislator’s representative or as a longtime community member or any other type of resource. Her name pin simply identified her as a “Rosie,” a designation she still says is inappropriate for her history.

Still, she resolved to “do all I could to restore those missing chapters.” She added, “That’s why I became a park ranger.”

If she doesn’t identify herself as a Rosie, saying the iconic image associated with the female industrial workers and reality of the construction effort are more associated with white women, she is hoping some of those who are Rosies will choose to make sure their stories are told with the same enthusiasm and determination as she has told what she knows. And if their “truths” differ from hers, Reid Soskin is at peace with that. “Where they coexist, that’s enough for me.”

As someone who speaks to visitors three to five days a week at the Richmond museum, she sees what she has accomplished.

“My fingerprints are all over that park. I did not know I was helping to shape a park, but I see my fingerprints all over. The story is expanded by my presence.”

Reid Soskin’s talk was presented Saturday in partnership with the Martinez Historical Society and the John Muir Association. Her book is published by Hay House of Carlsbad, www.hayhouse.com.

Leave a Reply