On Tuesday morning, Donald Trump posted the following on his Twitter account:

“Crime is out of control, and rapidly getting worse. Look what is going on in Chicago and our inner cities. Not good!”

Something about that didn’t seem right, so I checked crime statistics for both Chicago and for the nation as a whole. I turns out that the violent crime rate is roughly half what it was 20 years ago, in both Chicago and the rest of the country, and a graph of the crime rate shows a steady decline over that time.

It is also true that the most violent cities in America actually aren’t our largest cities – “inner” or otherwise. Some of the most dangerous communities in the country are small towns. For example, according to the most recent statistics from the FBI, the tiny burg of Oceana, West Virginia (population: 1,364) has a violent crime rate that is almost ten times the rate in Chicago. So, a tiny town in Appalachia with a 98 percent white population is a far more dangerous place than big, scary, multiracial Chicago.

What is true is that there was a massive, nationwide crime wave from roughly 1965 to 1995. The Nixon-era Republican Party blamed this wave on supposedly soft-on-crime, permissive liberals, and for 30 years sentencing laws and guidelines got tougher and tougher, without much discernable effect on the violent crime rate.

Then, in the mid-1990s, crime rates began a plunge that has continued ever since, and– despite the claims of Trump and others– shows no particular signs of slowing.

One intriguing hypothesis for why this might be has been offered by biochemists. They have discovered a very strong correlation between the level of lead in the environment and the level of violent crime.

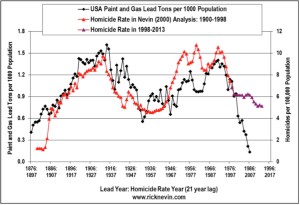

As you can see in the graph above, the rates track very closely. The two peaks on the graph are lead from paint, and lead from leaded gasoline, which correlate very closely with two peaks in crime in the 1930s and 1990s.

Lauren K. Wolf, a biochemist and Assistant Managing Editor of the trade journal Chemical and Engineering News, describes the research in more detail:

“Looking for explanations of the ’90s crime drop in the U.S., economists and crime experts latched onto these and other epidemiology studies. “We saw these correlations for individuals and thought, ‘If that’s true, we should see it at an aggregate level, for the whole population,’” says Paul B. Stretesky, a criminologist at the University of Colorado, Denver. In 2001, while at Colorado State University, Stretesky looked at data for more than 3,000 counties across the U.S., comparing lead concentrations in the air to homicide rates for the year 1990. Correcting for confounding social factors such as countywide income and education level, he and colleague Michael J. Lynch of the University of South Florida found that homicide rates in counties with the most extreme air-lead concentrations were four times as high as in counties with the least extreme levels (Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2001, DOI: 10.1001/archpedi.155.5.579).

“Others have found similar correlations for U.S. cities, states, and even neighborhoods. In 2000, Rick Nevin, now a senior economist with ICF International, saw the trend for the entire country (Environ. Res., DOI: 10.1006/enrs.1999.4045). In general, these researchers see blood-lead levels and air-lead levels increase, peak in the early 1970s, and fall, making an inverted U-shape. About 18 to 23 years later, when babies born in the ’70s reach the average age of criminals, violent crime rates follow a similar trajectory.”

Crime rates are currently at their lowest ebb since the early 1960s, so why is there still so much fear of crime?

I think part of the answer is that people older than about 30 or so remember, and acquired habits of thought due to, the crest of the crime wave 20 years ago, and have not yet fully adjusted to a radically changed world.

My father grew up in a lace-curtain-Irish enclave in southeast Chicago, and people in his neighborhood rarely locked their doors – to the point that his parents sometimes had trouble finding their house key, which was usually stashed in a drawer someplace and then forgotten about.

Another part of the answer is that the media often sensationalizes crime and gives the false impression that it is far more menacing than the facts would support.

Despite the fact that the current moment is by far the safest time in our history to be a child, there is a pervasive and somewhat absurd fear of children being harmed by strangers.

Child abductions are a real– if vanishingly unlikely– threat, but in his book “Protecting the Gift,” child-safety expert Gavin De Becker points out that compared to a stranger kidnapping, “a child is vastly more likely to have a heart attack, and child heart attacks are so rare that most parents (correctly) never even consider the risk.”

There has recently been an uptick in Chicago’s murder rate (though nowhere near the levels of the early 1990s) but despite Donald Trump’s fear-mongering, it is not a sign of a statistically significant trend. This is still the safest time in living memory to walk the streets of America.

Matt Talbot is a writer and poet, as well as an old Benicia hand.

Leave a Reply