THE BENICIA HERALD's office on First Street, Benicia, circa 1911.

Courtesy Benicia Historical Museum

1919: Episode 1

FOR ALMOST A YEAR NOW, every other Saturday afternoon Gail Westlake had been sending her son Jack to fetch a bucket of beer for her “gentleman caller,” Mister James Soames of San Francisco.

Though there were rumors in town that Soames was a married man and that his visits with a young war widow like Gail were shameful, Jack knew there was little he could do about it. “Best to leave sleepin’ dogs lie” was the advice his friend, Adam Tucker, had given him.

“Here’s the money,” Gail said, giving Jack a tin pail and a handful of coins, mostly pennies. “Hurry! Mister Soames will be here any minute.”

“Luigi won’t like this,” Jack protested. “He hates pennies.”

Gail looked sternly at her son. He had his father’s square jaw and wide-set blue eyes. It was a handsome face, but at moments like this she saw weakness. There was something furtive and desperate in Jack’s eyes. Like his father, he was too eager to win the approval of others. “Never mind what Luigi likes!” she retorted. “Get going!”

Jack made his way slowly along the wooden boardwalk on First Street until he came to the entrance of Campy’s Tavern. Because it was a hot August day, the bartender, Luigi Berico, had wedged the door open to keep a cross draft from the open windows at the rear of the barroom. The only patrons in Campy’s at this early afternoon hour were half a dozen farmers from out of town. Berico was engaged in animated conversation with one of them when Jack entered.

Placing his bucket on the bar top, Jack gazed around the dark and sparsely furnished interior of the place. Apart from the long bar itself, there were only a few battered wooden tables and chairs. The only décor consisted of four trophy elk antlers hung haphazardly against the long wall opposite the bar.

There was one feature of Campy’s Tavern that fascinated Jack, though. To discourage patrons from spitting on the floor, Campy’s brother-in-law, a plumber by trade, had installed a long metal trough on the floor directly in front of the bar. A steady stream of water flowed through this trough and emptied into a drain near the front entrance.

As he waited for Luigi, Jack suddenly noticed a five-dollar bill floating toward him in the trough. Checking to make sure no one was watching, Jack quickly reached down, picked up the bill, and stuffed it in the back pocket of his overalls.

Jack’s swift movement attracted Berico’s attention. “What d’ y’ want, kid?” he shouted.

Jack pointed to the empty bucket on the bar top. “Mom wants a bucket of beer.”

“Oh yeah?” Berico asked sarcastically as he ambled toward Jack. “And did your Momma give you the money to pay for that bucket of beer? Thirty-five cents, y’ know.”

Grimacing, Jack dumped his handful of coins on the bar top.

Angrily, Berico grabbed the bucket and quickly filled it from a barrel tap. Before giving the foaming bucket to Jack, though, he slowly and methodically counted each coin and dropped it into the till behind the bar. Jack had watched Berico go through this insulting ritual many times before. This time, Jack didn’t care. All he wanted now was to escape from Campy’s Tavern before one of the farmers realized he had lost his five-dollar bill.

On the street again, Jack carried the heavy bucket as fast as he could back to his mother’s second-floor apartment. As he climbed the outside stairway, he heard the tinkling sounds of Gail’s upright piano. She was playing one of her favorite ragtime tunes, her long fingers flying over the keys with joyful abandon. His mother was happy. Obviously, James Soames of San Francisco had arrived.

A tall, lean man with slicked-down black hair, a tiny moustache and shifty green eyes, Soames was lounging in his mother’s favorite mohair armchair when Jack entered the apartment. He had removed his coat, collar, and tie and was cooling himself with a hand-fan Gail had given him. He nodded a perfunctory greeting at Jack but concentrated on fanning himself.

“Did you bring Mister Soames his beer, Jack?” Gail asked as she continued playing.

Jack lifted the bucket onto the kitchen counter, slopping some of its contents on the floor.

“Be careful, Jack!” Gail scolded. Abruptly, she stood up from her piano stool and ladled beer into a ceramic mug for her guest. As she handed the mug to Soames, Gail said softly, “You may go out and play now, dear. Just stay close by so I can call you from the window.”

Jack did not reply. It was all part of the routine. His mother always sent him out to play whenever Soames came to visit. He knew she didn’t really care how far he roamed in the streets of Benicia, as long as he returned by suppertime.

Besides, Jack was eager to tell his friends about the treasure he had found. Five dollars was more than some grown men earned in a week. He could buy just about anything he wanted. The only problem was what — a Daisy air rifle, a shiny new Montgomery Ward bicycle? These were things Jack had always wanted but his mother could never afford. Even if he bought both of them, he might still have money to spare.

Because it was Saturday, First Street was busy with traffic. Scores of vehicles — from buckboard wagons drawn by old nags to new Model Ts — were trundling up and down between Military Road to the City Dock at the waterfront end of First Street, where several vehicles were now lined up to take the car ferry across the river to Martinez.

In 1919, Benicia was a hub of commerce for farmers who brought their grain, nuts and fruit there for shipment by train to Oakland and beyond, shopped for tools and clothing at Wilson’s Dry Goods, and purchased their harnesses, boots and saddles at McClaren’s Tannery. While the farm wives shopped, many of their husbands would visit local saloons like Campy’s Tavern, The Pastime Card Room, or Wink’s Bar. There were more than eighteen of these establishments on First Street, especially close to the waterfront.

The air was filled with dust from the sun-baked dirt surface of First Street — dust that, on a hot summer day, could be as thick as the fog that rolled in through the Carquinez Strait from San Pablo Bay during the winter months. Everywhere you looked, there was dust — especially on people’s boots and shoes, Jack noted, as he stepped down into the street from the wooden sidewalk.

“Watch where you’re goin’, boy!” an angry driver shouted at him as Jack barely missed being struck by the fender of a passing flatbed truck.

His friend, Del Lanham, was waving at him from the stoop in front of Wilson’s store. “Hurry up, Jack. I want to show you something.” She ran into the store ahead of him.

Del was different from most other girls Jack knew. Even though she usually wore a pinafore, Del preferred overalls so she could do daring things like climb to the top of the big water tower near the railroad tracks and throw rocks at the turkey buzzards when they flew low over the tule flats.

It was dark and cool inside Wilson’s Dry Goods store, which was full of interesting smells and sights — everything from sweet-smelling spices and local-grown apples to shiny new shovels and headless wire dummies displaying women’s outer garments. Del stopped in front of the big glassed-in display case where Wilson had filled several wooden trays with penny candy.

“Look, I have some money!” Del declared, holding up two shiny quarters. “We can buy us a whole bunch of candy with this!”

Jack wanted to say he had some money too — a lot more than Del! But he decided to say nothing. After all, Del’s father was a courtroom judge and owned two cars and a big Victorian house on West G Street. He and his daughter could well afford to be generous.

Then he saw it. On a shelf high above the candy counter sat a sleekly varnished wooden box with an iron footrest on its top. Instantly, Jack knew how he would use his five-dollar bill. He would buy that shoeshine kit and start his own business. What better place to do it than here in Benicia? There were bound to be hundreds of shoeshine customers in a town where one of the biggest industries was McClaren’s Tannery.

“So what kind do you want?” Del asked, startling Jack out of his train of thought.

“Ahm … let’s see,” he answered, studying the trays full of multi-colored gumballs, black licorice sticks, chunks of chocolate fudge, and cherry-colored jawbreakers. “I’ll take five licorice and ten of them jawbreakers.”

“You mean those jawbreakers,” Del corrected.

Del was always doing that, Jack thought resentfully — correcting his grammar or telling him how to pronounce some new word he tried to use. He supposed that was because Del was a teacher’s pet at Saint Catherine’s Seminary.

He put up with it, though, because Del was a good friend. She was always generous about sharing things.

1919: Episode 2

“HELLO THERE, MISSY,” Vernon Wilkie chirped as he leaned over the counter and grinned at Del. “What do ya wanna buy today?” Wilkie was one of the clerks who worked in Wilson’s store. He was a scrawny little man with buckteeth and one eye that constantly twitched.

“Five licorice, ten jawbreakers, and fifteen gumballs, please.” Del loved gumballs because she could blow bubbles with them. In fact, Jack thought, she could blow bigger bubbles than anyone else he knew.

Wilkie dropped the candy into a brown paper bag and handed it to Del. “That’ll be thirty cents, Missy.”

Del gave Wilkie the two quarters. “Kaching!” sounded the cash register behind the counter. Wilkie dropped the quarters into the till and handed Del two dimes in change. These she put into the snap-purse she always carried in a side pocket of her pinafore. Turning to Jack, she said, “Come on. Let’s go down by the dock to eat our candy.”

Jack stood his ground. “No. I wanna buy something else first.”

Del looked at him in astonishment. “What do you mean?” she demanded. “You can’t buy anything. You don’t have any money.”

“That’s what you think,” Jack said as he reached into his pocket and pulled out the still-moist five-dollar bill.

“Where’d you get that?” Wilkie demanded. “You didn’t steal it from your Momma, I hope!”

“I didn’t steal it,” Jack said, keeping calm, even though he was very angry with Wilkie for accusing him. “I found it, and I want to buy that shoeshine kit up there.”

Wilkie shook his head, still convinced that Jack had done something dishonest. “Lemme see that bill.”

“Not ’til you let me see that shoeshine box first,” Jack insisted.

Again Wilkie shook his head suspiciously. “I s’pose I could let you see it,” he admitted. Pulling a step-stool from under the candy counter, he climbed up to take the shoeshine box down from its shelf. Then, keeping a firm grip on the box, he slid it across the counter toward Jack.

Jack reached inside and pulled out some of its contents, which included three small glass jars of differently colored shoe polish, two flannel rags, and two stiff-bristled shoe brushes. After carefully examining each of these items, Jack placed his five-dollar bill on the counter.

Wilkie quickly reached for it. As soon as he felt its moist surface, he drew back his hand. “Where’d you get that slimy thing — outta somebody’s privy?”

Del promptly leaned over the bill and sniffed it. “Nope. Doesn’t smell like it to me,” she announced with a defiant grin.

“I ain’t pickin’ that thing up with my bare hands!” Wilkie declared. “You’ll jus’ have to wait ’til I get a rag or somethin’ t’ clean it off.” Taking the shoeshine box with him, he disappeared into a room at the back of the store.

“Don’t know why he’s so fussy,” Jack said to Del as he retrieved his bill and stuffed it back in his pocket. “Money’s money, ain’t it?”

“Isn’t it,” Del corrected. But she did so with a smile that told Jack she agreed with him. “So where’d you find it?” she asked.

“In the spittoon trough at Campy’s.”

“Eeww! You mean you just picked it up out of a filthy trough?”

Jack nodded. Then, noticing that Wilkie was returning, he put his index finger to his lips. “Shhh!”

Wilkie came back to the front of the store, still clutching the shoeshine kit in both hands, along with a clean dustrag. “Now,” he said, “Lemme see that bill.”

Jack again put his five-dollar bill on the counter. Gingerly, Wilkie placed his dustrag on top of it and tried to wipe it dry. Then, with one finger, he flipped it over and tried to dry the other side. Next he picked the bill up with both hands and carried it over to the big store window where he carefully examined it in the light from the street. “Guess it’s alright,” he said at last and returned to open the cash register drawer and drop in Jack’s five-dollar bill.

“Wait a minute!” Jack declared. “You ain’t told me how much it costs yet.”

Wilkie looked surprised at first, but his expression quickly turned to anger. “Two dollars and fifty cents!” he snapped.

“That’s too much!” Jack retorted. “It’s nothin’ but an old wood box with some little jars, rags and brushes in it. I could buy them things separate for a lot less.”

“So go ahead!” Wilkie growled and slammed the cash register drawer closed. “I ain’t sellin’ this kit for one penny less!”

“Then gimme my five dollars back,” Jack said.

“What’s goin’ on here?” another voice asked. It was Cliff Wilson, the store owner. Wilson was a big man who moved and talked very slowly, as if he were never in a hurry to do anything.

“This kid comes in here with a filthy old fiver and tells me he won’t pay for this shoeshine kit he wants,” Wilkie whined.

“Why not?” Wilson asked.

“He says it costs too much.”

Wilson took the shoeshine box from Wilkie and held it up to look for the price tag he himself had pasted to the bottom. “Dollar forty, it says here.”

“That isn’t what Mister Wilkie told Jack!” Del angrily protested. “He said it was two dollars and fifty cents.”

Wilkie’s face turned white with fear.

“Well,” Wilson said without so much as glancing at his store clerk, “the price tag says a dollar forty. You want it for that price, young man?”

“Yes sir,” Jack said.

“Give the boy his change and wrap that shoebox up for him,” Wilson said to Wilkie. He then calmly walked back to the rear of the store.

“Sorry, kid. Guess I shoulda checked the price tag,” Wilkie muttered grudgingly as he handed the wrapped package, and three dollars and sixty cents in change, to Jack.

“You better be careful, Mister Wilkie,” Del warned as she and Jack walked out of the store with their purchases. “Guess you showed him!” she whispered triumphantly to Jack.

“Aw, forget it,” Jack said. “Let’s go see what Adam’s doing.”

1919: Episode 3

ADAM TUCKER WAS AN AFRICAN AMERICAN who had been a munitions and motor pool officer stationed at the Benicia Arsenal during The Great War. He was discharged from the Army in 1917 because an accidental explosion had blown off his right hand. An Army surgeon replaced it with a steel hook.

In spite of his handicap, Tucker was a skilled auto mechanic. He knew more about car repair and could do more with his left hand and his hook than almost any other skilled artisan in the North Bay. People from miles around went to Tucker whenever they needed work done on their wagons, cars or trucks.

Many children and teenaged boys in town liked to watch Tucker while he worked on the vehicles in his garage, which was in an old blacksmith’s shop on West H Street. The young people were fascinated by the mysteries of the combustion engine and the skill with which Tucker could manipulate tools with his hook. A patient and gentle man, Tucker didn’t mind the spectators as long as they didn’t get in his way or stand too close to his mechanical equipment.

“Whose car are you working on, Mister Tucker?” Del asked as she and Jack stood in the open doorway of his garage.

Tucker, who was leaning over the engine compartment of a 1917 Model T Touring Car, did not look up from his task. “This be Miss Ebert’s car. Gotta fix her carb’retor,” he explained.

Not knowing what a carburetor was, Del simply said, “I see.” She didn’t want Tucker, or either of the two teenaged boys who were standing near her, know how ignorant she was.

So she whispered in Jack’s ear, “What’s a car brator?”

“How should I know?” Jack said out loud.

One of the teenagers, Calvin Watrous, laughed derisively. “Carburetor’s what feeds gas to the engine,” he explained superciliously.

Del felt her face turn red with embarrassment.

“Well no, Cal. Actu’ly it don’t just do that,” Tucker corrected, straightening up and looking around at his young admirers. “Carb’retor mixes gas with air. You got to have air to ignite the fuel. I had to put a new float in this one.”

Del stuck her tongue out at Calvin.

“Let’s see if she works now,” Tucker said as he shoved a hand crank into the slot under the radiator at the front of Miss Ebert’s car and gave it a quick turn with his left hand. The engine sputtered several times but did not start. Tucker cranked it again. This time, the motor rattled into action. Again, Tucker leaned over the engine block and adjusted something that made the engine run more smoothly. “Guess she’s all fixed,” Tucker announced and closed the metal hood. Then, turning to Del and Jack, he asked, “You two wanna take her for a tes’ ride?”

“Sure!” Del and Jack said simultaneously.

“How ’bout me?” Calvin protested.

Tucker gave him a stern look. “You boys stay here with Billy and guard the garage.”

Billy Sparks was a 17-year-old mixed-race boy — people around town called him a “mulatto” — who worked as Tucker’s apprentice. The rumor around town was that Billy was Tucker’s son, though nobody had any proof of that and Tucker himself claimed the boy was an orphan.

Tucker opened one of the backseat doors of the Model T. “Hop in, you two. We’s off an’ runnin’!”

As soon as Jack and Del climbed in, Tucker closed the door. “Don’t you be touchin’ them door handles, now,” he warned. “You can fall out an’ get hurt.”

“We won’t. We promise, Mister Tucker,” Del assured him.

Nodding his approval, Tucker climbed into the driver’s seat, released the hand brake, and slowly eased Miss Ebert’s Touring Car out toward the heavy traffic on First Street. Turning right, he drove the vehicle toward the waterfront.

Jack and Del were excited. They waved proudly at all the pedestrians they passed on the street. Several people gave them dirty looks, appalled that two white children would be riding in a car driven by a Negro.

“She sounds pretty good,” Tucker announced proudly. But then, suddenly, the car’s engine began to sputter again. “Uh-oh!” Tucker exclaimed. “Somethin’ wrong.” As the engine stalled out, he guided the vehicle toward the side of the street, where he locked the hand brake and stepped out of the car. “You stay put while I check to see what’s wrong,” he said.

Tucker opened the hood and examined the fuel line. “Well, I’ll be!” he declared. “I do believe she’s out o’ gas. You two stay here while I goes back n’ gets us a can. Don’t you be touchin’ nothin’ now!” he warned again as he headed back up the street toward his garage.

“Want a gumball?” Del asked, reaching into her paper bag to add to the two she was already chewing.

“Nah,” Jack said. “I don’t like them things. They’re too sweet. Gimme a licorice.”

“Those things,” Del corrected as she drew a black licorice stick out of her paper bag. “And you should always say ‘please,’” she added.

“Please, Miss Lanham — can I have a licorice stick?” Jack mocked.

“You may, Mister Westlake,” she replied with equal sarcasm. They both giggled.

For the next several minutes they sat contentedly chewing and watching the busy activity on First Street. “Have you heard about the big parade next Sunday?” Del suddenly asked.

Jack nodded. “Mom told me about it. She said it’s to celebrate the new law against drinking.”

“That’s not all it’s about,” Del said. “It’s also about women’s suffrage.”

“What’s that?” Jack asked. He had heard the term before, but he had no idea what it meant.

Del gave him a withering look. “Women’s right to vote. It’s another new law they’re passing. It’ll mean every woman over 21 can vote. Papa says he thinks it’s a silly law, but I think it’s wonderful.”

“Why?” Jack asked.

Before Del could answer, their conversation was interrupted.

“Where’s the driver of this car?” a deep male voice asked. Startled, Jack and Del looked up to see a tall man in a dark blue uniform leaning in over the steering wheel. It was Constable Frank Cody, a man whom Jack immediately recognized because he had often seen him patrolling the street in front of Campy’s Tavern.

“He went to get some gas,” Del promptly answered. “He’ll be back soon.”

“Who is he?” Cody asked, pulling a booklet out of his back pocket and starting to fill in a summons form.

“Oh, please don’t give him a ticket, sir,” Del begged. “It’s Mister Tucker. He just fixed Miss Ebert’s car and was taking it for a road test.”

“He didn’t know it was out of gas ’cause Model T’s don’t have gas gauges,” Jack explained, hoping to impress both Del and Cody with his knowledge of automobiles.

The constable acted as if he did not hear them. He finished filling out the summons, tore out a copy and dropped it on the driver’s seat. “You tell Tucker t’ test his cars someplace else. First Street ain’t no place for test drives.”

“But he isn’t driving it now,” Del corrected. “He just parked it here for a few minutes to go back and get some gasoline.”

“Ain’t no parkin’ on First Street neither,” Cody said with a sly smile.

“What do you mean?” Del demanded angrily. “Look at all these other cars parked along here. People can park their cars anywhere they want.”

“Regular people maybe,” Cody snarled, “but not niggers like Tucker.” Having made his point, the constable walked on down the street.

“He’s terribly mean!” Del declared. “I’m gonna tell Papa.”

“Won’t do any good,” Jack said. “That’s Frank Cody. He’s the mayor’s son.”

“We’ll just see about that!” Del retorted.

When Tucker returned with his can of gas and saw the summons, he quickly stuffed it into his overalls pocket. Then he poured gasoline into the tank of the car and cranked the engine again.

Del tried to tell him how mean Constable Cody had been, but Tucker waved his hand indifferently. “Don’t pay it no mind, Miss Del.”

“I’m still telling Papa,” Del insisted. “It’s not fair!”

1919: Episode 4

BEHIND THE STEERING WHEEL AGAIN, Adam released the handbrake and carefully eased the Touring Car into traffic. At the next intersection, he turned right and drove around the block. As they pulled into the garage, Jack suddenly realized he did not have his shoeshine box.

“Where’d you leave it?” Del asked anxiously. “Hope nobody stole it.”

“I think I left it on the ground when we got into the car, right near where we were standing,” he told Del.

“Don’t you be worryin’, boy,” Adam said. “We fin’ it.” He called out to Billy, who was working the metal lathe. “Billy, you seen a package layin’ aroun’ here?”

Billy did not look up from his work. He simply gestured toward some large open shelves along the back wall of the garage.

“Tha’ she is,” Adam said as he retrieved Jack’s package from a collection of cans and small engine parts on one of the shelves and handed it to Jack.

“Thanks, Mister Adam,” Jack said. Then, turning to Del, he asked, “You think your Papa’d mind if you took it home with you and kept it at your house?”

“Why?” Del asked. “Don’t you want to take it with you?”

“I don’t want Mom to see it,” he explained. “She’ll ask too many questions about how I got it, and I don’t want her to know.”

“Why not?” Del demanded. “You didn’t steal it, so why worry?”

“Well, no. I didn’t steal it. But she’ll want to know where I got the money to buy it. And then she’s liable to say I should take it back to Wilson’s and get my money back and then give the whole five dollars to old man Campy.”

“That’s silly!” Del declared. “You didn’t steal that money. You just got lucky and found it. Finders keepers.”

“You don’t know Mom. She’s very particular about things like that. ‘Honesty’s the best policy,’ she always says.”

Del still thought Jack was being foolish, but she decided not to argue. Instead, she asked, “So what do I tell Papa? You know he’s going to want to know why I’m keeping that package for you.”

Jack thought for a moment, then said, “Why don’t you just tell him it’s a surprise birthday present for your teacher at school or something?”

“That’s an even sillier idea!” Del declared. “You know he’s going to ask me what’s in the package.”

“Never mind,” Jack said and started to leave with his package.

Adam, who had been standing and listening to this dialogue, intervened. “You can keep it here if you want, Jack,” he suggested.

Jack’s face lit up. “I can? Gee, Mister Adam! Thanks!”

Adam smiled and put the package back on the shelf. “You can come get it any time you want,” he said. “It’ll be safe, an’ I won’t tell nobody.”

“He’s such a nice man,” Del said as she and Jack left the garage and walked back toward First Street.

“That’s because he knows what it’s like to be poor,” Jack observed.

“What do you mean?”

“When you’re poor, you got to keep secrets,” Jack answered, “’cause people are always trying to steal from you.”

“Why would they want to steal from you if you’re poor?” Del giggled.

Jack did not respond. He decided Del would probably never understand.

Just then, they heard the sound of a train whistle. “Oh, that’s the 5:15!” Del exclaimed. “I’ve got to go now, or Papa will be very angry.” Immediately, she ran to the corner and down First Street toward home.

The traffic was even heavier now as Jack walked slowly south on First Street. Most of the pedestrian and vehicular traffic was moving toward the Benicia depot as people rushed to meet the passenger train from Sacramento.

Unlike Del, Jack was in no hurry to get home. He knew his mother would be in a bad mood when he returned, as she always was after a visit from Soames. Often on such occasions, he had found her sitting in her mohair armchair, weeping.

Jack didn’t understand exactly why his mother acted the way she did, but he did not like to be around her when she was unhappy. He decided to walk down to the depot and watch the switch engine push the passenger cars onto the train ferry that would carry them across the river to Port Costa.

Walking past the entrance of Campy’s Tavern again, Jack noticed the place was now filled to capacity with boisterous male patrons. By sundown, many of them would start reeling across First Street toward the Lido — the largest of several bordellos located near the railroad depot. On either side and to the rear of this two-story building, rows of small private rooms, or “cribs,” had been erected where the women who worked at the Lido would entertain their customers.

The Lido was a source of considerable embarrassment to many upright citizens. But as it had long been one of the most successful business enterprises in Benicia, the town fathers had little alternative; all they could do was confine and control the nefarious activities at the Lido through strictly enforced zoning laws. To protect the health of Benicia’s citizens, they also passed an ordinance requiring that the Lido’s proprietor, Mrs. “K.T.” Parker, send all her female employees to a local physician for weekly checkups — a requirement with which Parker was perfectly willing to comply, since it enhanced the quality of her services.

Jack and his friends always stayed on the opposite side of First Street when they passed the Lido, for parents, teachers, preachers and policemen constantly warned that severe punishment would be meted out to any minor who so much as exchanged a civil word with Mrs. Parker or one of her “girls.” Even so, 9-year-old boys like Jack couldn’t resist sidelong glances at the attractive young women who often waved at them from the second floor bay windows of the Lido.

The depot was crowded when Jack got there. Hundreds of people were greeting newly arrived passengers from Sacramento or bidding others farewell as they climbed aboard the Pullman cars. Porters scurried here and there with luggage, and trainyard workers shouted to each other as the locomotive was decoupled from the front of the passenger train and moved slowly onto a sidetrack.

Jack loved the sound of hissing steam the huge engine made as it moved, its enormous steel wheels revolving slowly but potently, its connecting rods sliding back and forth like the limbs of some giant preparing to charge.

Even as he lay in bed at night, Jack took comfort in the hooting, clanging and chugging racket the steam locomotives made only a few hundred yards from Mrs. Brown’s boarding house where he and his mother lived. They evoked an almost supernatural power that he felt driving relentlessly forward within himself. They were both the monsters and the angels of his boyhood dreams.

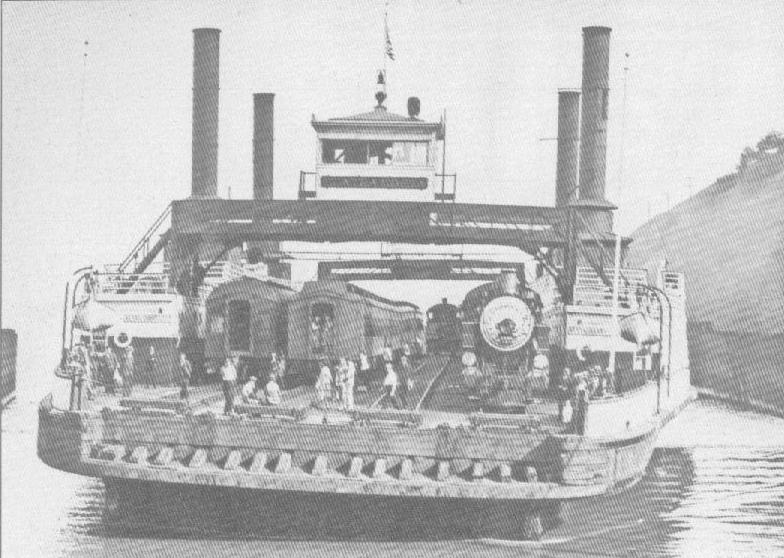

Jack joined the crowd of spectators at the waterfront end of First Street to watch as the passenger cars were slowly pushed aboard the Solano — one of the two large ferries that carried rolling stock across the Strait.

Loading the Solano was an arduous and time-consuming task. The passenger cars in the original train had to be pushed aboard in coupled sets, each on one of four parallel tracks built onto the ferry deck, as long and wide as a football field. After each set of cars had been pushed into place, it had to be uncoupled. Then a switch engine pulled back the rest of the train so the next set of cars could be pushed aboard on a parallel track.

Jack yearned to watch these mechanical operations, but there were so many others already crowding for a view that it was impossible for him to get close enough. He decided to walk to the other side of the depot so he could at least watch the switch engine as it moved backward and forward on the tracks approaching the ferry.

As he passed the waiting platform, Jack overheard the conversation between a young couple who had apparently just gotten off the train from Sacramento. The man was wearing a two-piece white linen suit and a Panama hat. The woman wore a canary yellow dress and carried a matching purse and parasol.

“Good heavens!” the woman complained. “What a dreadful smell! What is it?”

“I have no idea,” her companion replied. “Perhaps we should get back on the train instead of waiting here.”

“Yes, let’s do!” the woman said as she led the way back down the steps.

Jack couldn’t help smiling at this conversation. It was obvious these travelers had never stopped in Benicia before. Like most newcomers, they were reacting to the rancid odors coming from McClaren’s Tannery.

They did not realize that, inside the five-story brick building just a few blocks away, teams of men was busily scraping hair and flesh from the hides of recently slaughtered cows, horses, pigs and goats — the first step in a manufacturing process that created a horrid stench in Benicia, both day and night.

But then Jack noticed something much more offensive. His mother’s friend Soames was standing near the entrance to the Express Office, flirting with one of the pretty young women who worked at the Lido.

Now he understood why his mother was unhappy whenever Soames came to visit.

1919: Episode 5

THOUGH IT WAS SUNDAY, Del awoke an hour before sunrise. As she knelt beside her bed to say her morning prayers, she heard the seals barking out on the water. Quickly she ran to the window, hoping to glimpse some of the creatures frolicking close to shore.

But the faint light of pre-dawn was only beginning to define the eastern horizon. The shoreline at the foot of the bluffs in front of Del’s house was still completely shrouded in darkness. All she could see were the lights at the train ferry terminal a quarter of a mile away and, more than a mile away on the opposite shore of the river, the flickering lights of Martinez.

Del knew the seals were not far out there in the darkness, though. For it was August — the time of year when millions of salmon crowded through the Carquinez Strait and rushed up the Sacramento River to their spawning pools. The predatory seals were always in hot pursuit of this sumptuous fare. Feeling compassion for the desperate salmon, Del murmured a prayer to their patron, Saint Francis. Then, putting on her bathrobe and slippers, she tiptoed down the staircase, careful not to wake her father.

Because it was Sunday, their live-in housekeeper, Ruby Hicks, had the day off so she could perform her duties as Head Deaconness at the Evangelical Baptist Church in Vallejo. Del would have the whole house to herself for at least an hour. Very quietly, she crept into the kitchen pantry, where she knew she would find the bowl of cherries Ruby had picked the day before. Taking a large handful, she went into her father’s study to find something interesting to read.

Next to her own bedroom, her father’s study was Del’s favorite room in the house — even though it often reeked from the stench of his cigars. With its high ceiling, dark mahogany paneling, and comfortable Mission-style armchairs — as well as its three tall windows looking out onto the street and back yard — her father’s study made a wonderful retreat.

Two full walls in Judge Lanham’s study were covered floor-to-ceiling with bookshelves crammed full of thick, leather-bound volumes. Most of these were books about California law and history. But there was a special low-level shelf the Judge had reserved for Del containing books he considered appropriate for a nine-year-old girl to read. Among the titles he had chosen were Bronte’s “Jane Eyre,” Defoe’s “Robinson Crusoe,” London’s “Call of the Wild,” and Stevenson’s “Treasure Island.”

Del had already read many of these books, even though her Aunt Lucy thought most of them more suitable for older readers. Del had not yet tried one of the newest additions to her special library — Burnett’s “The Secret Garden.” She decided the title looked interesting. Pulling this volume from its shelf, she sat down in her father’s large, leather-cushioned armchair and, within minutes, was completely absorbed.

Two hours later, her father suddenly appeared in the doorway to his study. “Adelaide, hurry and get dressed! It’s time to go to Mass! Didn’t you hear me calling you?”

Surprised that she had not even heard the hourly chiming of the big grandfather clock in the front hallway, Del immediately jumped up. “Oh! yes, Papa,” she said. “But this is such a wonderful book. Why didn’t you tell me about it?”

Her father walked over and took Burnett’s novel from her hands. Looking at its title, he said, “Hmm — ‘The Secret Garden.’ I’m afraid I’ve never read this book. Your Aunt Lucy recommended it to me. I’m glad you’re enjoying it, my dear. But we really must be going now. I’ll wait for you in the car.” As Del rushed upstairs to her bedroom, the Judge called after her, “Don’t dilly-dally,” he ordered sternly.

Unlike most Benicians, Judge Lanham owned two cars — a 1916 Model T Roadster and a 1915 Twin Six Packard Phaeton. The latter was a huge and powerful black four-door sedan and was the envy of everyone in town. Judge Lanham kept both vehicles in a large car barn in his back yard.

This morning, he chose to use the two-seat Roadster because it was only a short drive from his home on West G Street to St. Dominic’s Church on East I Street. Parking the much larger Phaeton would be a great nuisance. Besides, though proud of his possessions, the Judge was averse to ostentatious displays of any kind. He considered it unbecoming to a seated member of the Solano District Court Bench.

Del thought differently. She liked nothing better than to be seen driving through town in her father’s big Phaeton. She was very disappointed when she learned they were driving to Mass in the much humbler Roadster. “Oh Papa!” she declared. “I do wish we could ride in the Phaeton.”

“The Phaeton, young lady, is only for long trips,” her father said emphatically.

It didn’t take long for Del to spot her friend Maggie in the crowd of people leaving St. Dominic’s Church after Mass that morning because Maggie’s father, George Woolsey, was one of the tallest men in the parish. As President of the Bank of Italy on First Street, he was always stopped after Mass and engaged in lengthy conversation by the pastor and one or more of the parishioners who did business with George’s bank.

As soon as she saw Del, Maggie boasted, “Guess what! My sister Colleen’s going to be The Temperance Queen in the parade next Saturday. She’s the prettiest girl in town. Everybody says so.”

“Oh, that’s wonderful!” Del declared, trying to sound enthusiastic even though she did not at all agree Colleen Woolsey was the prettiest girl in Benicia. There were many others who were prettier — even some of the young women who worked at the Lido! Del would never say that to her friend Maggie, however. “Is there going to be a marching band in the parade?” Del asked, hoping to change the subject.

“Of course. Momma says there’s going to be lots of marching bands. There’s the drum and bugle band from the Arsenal, of course. And then there’s the Benicia High School band, the Navy band, and even Doc Blackburn’s Montezuma Minstrel Band from Vallejo.”

“A minstrel band?” Del asked, astonished that such a group would be allowed to participate, for many of its members were Negroes.

“Yes. They’re going to march in front of the John Barleycorn float. Momma says the float’s going to be fixed up to look like a hearse with a coffin inside and inside the coffin they’re going to put a dummy dressed up like John Barleycorn and the minstrel band’s going to play a funeral march — just to make fun of people who drink liquor.”

“That’s silly!” said Del, recalling her father’s disparaging remarks about the 18th Amendment. “John Barleycorn’s just an imaginary character in one of Jack London’s books.”

“No it’s not!” Maggie retorted. “Momma says it’s very serious and thank goodness they passed the new law so now there’ll be no more drunks.”

Del had to admit that it would certainly be better if they got rid of all the drunks in Benicia. Even her father would agree with that. “Well, I hope your Momma’s right,” she said.

“Momma’s always right!” Maggie declared, astonished that her friend could think otherwise.

At this point, Maggie’s older sister Colleen interrupted their conversation. Grabbing Maggie’s wrist, she commanded, “Come on, Maggie. We’ve got to go now.”

Del was furious. Colleen had been terribly rude. She had not even said hello to Del. “Prettiest girl in town indeed!” she fumed.

1919: Episode 6

AS WAS CUSTOMARY for several of Benicia’s more prosperous families, after church on Sundays Del and her father brunched in the formal dining room of the Palace Hotel on the corner of First and H streets. Locally, the Palace was billed as “Benicia’s only first-class hotel.” Its two upper floors of side-by-side bay windows rose above its covered ground-floor esplanade like the tiers of a giant wedding cake.

The walls of the Palace Hotel dining room were decorated with murals depicting scenes of the Carquinez Strait when the indigenous Patwin Indian tribes had fished for salmon and shad in its swift-moving waters and hunted the beaver, elk, and grizzly bear that roamed and foraged freely in the surrounding marshes and hills. Del particularly liked the mural closest to the table where she and her father were now sitting. It depicted a Carquinez hunter crouched in his balsa canoe, poised to launch his spear at a beaver swimming in the tules.

Del’s imaginings were suddenly interrupted by the loud contralto voice of Florence Henshak. “Hello there, Clyde!” she trilled flirtatiously from two tables away where she was sitting with her husband, Oscar, and their two children — fifteen-year-old Rowena and nine-year-old Greg. “Why don’t you come join us?”

Greg was one of Del’s best friends, but she did not like Florence Henshak. Though superficially cheerful and solicitous, Florence would explode in a rage at the slightest provocation. She bossed her husband and children around mercilessly and constantly bragged about the famous people she knew.

Judge Lanham waved cautiously at the woman and focused on the menu the waiter had just given him. Florence Henshak was not to be ignored, however. Standing up, she called across the dining room, “Don’t be standoffish, Clyde! Come over here and sit with us.” To this loud command several other patrons in the dining room reacted with scornful stares. Del felt terribly embarrassed.

“I suppose we really should accept her invitation, Adelaide,” the Judge murmured sheepishly. Rising from his chair, he motioned Del to follow him to the Henshaks’ table. “Are you quite sure we’re not imposing?” he asked as they approached.

“’Course not!” Oscar said offhandedly. Although Oscar Henshak was in his late forties, with his plump, clean-shaven face and full head of flaxen hair he looked not a day over thirty. Without standing up to greet his guests, Oscar signaled the waiter to bring two additional chairs for their table. Then, nodding indifferently at Del, he resumed eating his plate of oysters. “Plenty o’ room,” he somehow managed to say with his mouth full.

“How are you, my dear?” Florence asked, embracing Del as if she were a long-lost relative. “We haven’t seen you in ages. Where have you been hiding all this time?”

Caught short by this question, Del looked desperately at her father. She had no idea how to answer.

“Del hasn’t been hiding, Florence,” the Judge said firmly. “She has been very busy this summer helping Ruby around the house. She’s old enough now to take on some of the household chores.”

Del couldn’t help smiling. Her father rarely if ever asked her to perform household chores. Raised in a Victorian household himself, Clyde Lanham believed female children should be treated as hothouse flowers.

There were several reasons why Del and her friends rarely visited Greg Henshak at his parents’ house. For one, it was almost a mile north of town, high in the hills overlooking Benicia. A sprawling two-story ranch house, it had scores of rooms and hired help, including two maids, four groundskeepers, a cook and a butler. That was another reason for the infrequency of Del’s visits — all those servants monitoring everything.

What made Del and her friends most uncomfortable, though, was Florence’s constant bullying and cajoling. “Stay away from the horse and car barns, children!” she would warn. “And don’t you dare go near my perennial gardens! No tree climbing and no running around in the yard or the house either!”

Now in the genteel dining room of the Palace Hotel, however, Florence Henshak was all sweetness and light. “Come sit here next to me, dear,” she urged as the waiter brought an extra chair for Del. “My! What pretty yellow flowers!” Florence gushed, touching Del’s coronet of daisies.

“They’re to show my support for Women’s Suffrage,” Del said, knowing full well this remark would not sit well with Florence, who believed very strongly that a woman’s proper place is in the home.

“I can’t imagine why a nice young girl like you would want to do that,” Florence snapped irritably. “Those suffragettes are just a bunch of hussies!”

“So who you puttin’ behind bars this month, Judge?” Oscar quipped as Del’s father sat down beside him.

“Actually, I have an estate settlement hearing tomorrow,” the Judge replied. “There are no criminal charges involved — just some greedy relatives squabbling over their share of the spoils.”

Oscar snickered. “Oh, I know all about that! You shoulda seen what a mess we had when my old man died. Why, they was relatives comin’ out o’ the woodwork! Even one of our own servants tried to stake a claim. Didn’t do ’em no good, though, ’cause I had me one o’ the meanest lawyers in San Francisco. He chewed up all them phony claims in no time.”

Oscar Henshak III was the grandson of an entrepreneur who had hit the “mother lode” when gold was first discovered in California. The grandsire had made his fortune not from mining or panning gold but from selling camping supplies and equipment to the thousands of prospectors who poured into the state in 1849. In the years that followed the Gold Rush, Oscar’s grandsire had invested his profits in the railroad industry — adding even more to his wealth.

Oscar and his family were now living off this accumulated horde.

Del was desperate to correct the man’s grammar. How, she wondered, could such a wealthy man be so ignorant! But at least Oscar’s outburst had distracted Florence. For the woman immediately jumped into the men’s conversation with more details about the people who had tried to break her father-in-law’s will. This gave Del a chance to tell Greg about Jack’s good fortune. Leaning close to him, she whispered the story in his ear.

“What are you two conniving about?” Florence suddenly demanded.

“Oh nothing, Momma,” Greg said softly, his face white with fear.

“Then why are you whispering?”

“We didn’t want to interrupt you and Mister Henshak and Papa,” Del quickly explained.

“Hmff!” Florence expostulated. But a waiter had just placed in front of her a sumptuous plate of roast duck with orange sauce, au gratin potatoes, and fresh green string beans to which, along with a second glass of champagne, she now eagerly gave her full attention.

By the time dessert was served, Oscar and Florence Henshak had polished off a full bottle between them. Both were in a holiday mood when the Judge politely explained he had to return home to work on the next day’s court hearing. Del and her father made their escape with little fanfare.

1919: Episode 7

CAVE BEACH WAS LOCATED ONLY ONE BLOCK west of Del’s house, at the end of the boardwalk that ran from City Beach on West E to Rosario’s boat dock on West G. Unlike City Beach, which was a bona fide public facility complete with clean white sand and a row of wooden beach houses where bathers could change their clothes, Cave Beach was a shallow inlet that, at low tide, became a mud flat the size of two football fields.

Local residents referred to the area as “Cave Beach” because of a seven-foot-deep hole the waters of the Strait had carved out in the sandstone bluff adjacent to Rosario’s dock. It was rumored that lovers would meet in this “cave” for late-night trysts.

What attracted Del and her friends to Cave Beach on hot summer days was not the cave but the mudflat. Here boys from all over town would gather at low tide to launch their homemade wooden sleds and race each other by paddling across the broad swath of slippery brown muck. It was a messy sport, of which few respectable parents in Benicia (if they knew about it) would approve, for at the north end of Cave Beach a large, rusty pipe dumped raw sewage into the makeshift playground.

Wearing old overalls and sandals, Del had sneaked out of the front door that Monday afternoon while Ruby was beating rugs on the back porch. Knowing she would need a change of clothes, Del had stuffed her pinafore and a towel in a canvas bag. She would change later in one of the public beach houses.

As she walked down the boardwalk toward Cave Beach, she saw her friends Jack, Greg, Sam Geddis and dozens of other boys propelling their boards across the flat, shouting at each other to get out of the way and often colliding. Del ran to the edge of the mud flat and called out, “Jack! Let me borrow your sled!”

But Jack was too preoccupied with racing Sam across the flat. Then Del saw Greg, who was just about to launch his own board. “Greg, wait!” she commanded. “Ladies first!” she added, assuming Greg would respond to this reminder of his gentlemanly duties.

She was wrong. Though he had looked directly at Del, Greg simply waved and flopped down on his board. Then, paddling furiously, he propelled himself beyond the reach of her voice.

Crestfallen, Del decided she would have to wait until one of her friends was ready to share. She walked back along the beach toward Rosario’s wharf, climbed onto it, and sat gazing out across the Carquinez Strait. The broad expanse of water was as smooth as a glass mirror reflecting the bright blue sky of a cloudless summer day.

It was not always so. In early spring and late fall, the waters of the Strait were often roiled with white caps as strong winds swept in from the northwest. Every morning during the winter months, heavy fog rolled in from San Pablo Bay, completely obscuring the high green hills on the opposite shore.

No matter the season, Del delighted in the changing moods of the Carquinez Strait. Often she felt they complemented her own. Right now, she reveled in the stillness of the water and landscape before her. Indifferent to the frantic shouts of the mud-sledders, Del identified with the tiny bodies of two seagulls drifting soundlessly out on the water, and with the solitary turkey buzzard making slow circles in the sky directly overhead.

The staccato sputtering of a single-cylinder gasoline engine interrupted her reverie. Glancing in the direction of the sound, she saw the long white hull and canvas roof of Rosario’s twelve-passenger ferry approaching. Only one person was aboard on the vessel’s return trip from Port Costa. Miguel Rosario himself stood at the wheel in the stern of his converted whaleboat. “Oy, Francisco!” Rosario shouted as his vessel approached.

A door in the storage shed at the end of the long, narrow wharf popped open and a thin, shirtless boy with thick black hair ran out to catch the bowline Rosario threw at him. Bracing a foot against a piling, the boy strained to keep the boat from drifting farther.

Del had known this Irish orphan since he first cam to live with the Rosarios three years before. Miguel and his wife Inez had taken Francis in, primarily for his usefulness as a dockworker and farmhand. Like many residents of Benicia, Miguel was involved with multiple enterprises. He operated the small passenger ferry that daily transported railroad workers between Benicia and Port Costa, and he raised pigs on a hillside farm west of Benicia.

Despite being abandoned by both his parents when he was only five, Francis Flanagan was fiercely proud of his Irish ancestry. Rosario, being his boss and being equally proud of his own Portuguese heritage, insisted on calling him Francisco.

Del moved down the dock toward Rosario’s boat. “Hello, Mister Rosario. Hello, Francis.”

Rosario only grunted, his thick eyebrows knitted in a scowl.

“’Lo,” Francis answered without looking at Del. Francis knew he had to keep his full attention on the cranky old man in the boat who, at any moment, might bark some new monosyllabic command.

Rosario climbed awkwardly onto the dock, handed its stern line to Francis, and headed toward the storage shed. As soon as she saw Rosario enter the shed and close its door, Del asked, “What’s he do in there?”

“Drinks his rotten brandy an’ sleeps,” Francis snorted contemptuously as he secured the stern line to a piling.

“What were you doing in there?” Del taunted.

“Readin’ a book.”

“What kind of book?” Del asked, surprised. It had never occurred to her that an orphan boy like Francis would be interested in books.

“A book about engines. I wanna learn all ’bout ’em, so I can get a better job an’ make some damn money!”

“You want to be a mechanic like Mister Tucker?”

Francis glared at her. “Not like him. Better ’n him — way better! I wanna be like Henry Ford an’ make millions o’ dollars.”

“You’ll have to go to college for that,” Del cautioned.

Francis’s thin lips twitched a fleetingly sarcastic smile. “College — hell, no! That’s a waste o’ time. Ford didn’t go to no college, did he? All y’ gotta do is work on all kinds o’ diff’rent engines. There’s new engines bein’ invented ever day for all kinds o’ things. You take this little one-banger, for instance.”

Francis stepped aboard Rosario’s boat and pointed at the small gasoline engine mounted in the center of the hull. “You know where this come from?”

Del shook her head.

“Out of a 1912 REO run-about Tucker found in a junkyard someplace. All he did was clean that old engine up an’ add a few new parts. Then he put a chain pulley on the flywheel and run it over a homemade drive shaft to turn the prop. Runs like a charm! Hell I could do that easy!”

“Do you really think so?” Del asked.

Before Francis could answer, Del heard Jack calling to her from the edge of the mud flat. “Hey, Del! You wanna use my board now?”

Del turned and jumped off the dock. “Bye, Fancis. See you later,” she said and ran toward Jack.

Francis shook his head in disgust. “Stupid girl!”

1919: Episode 8

THE SUN WAS SINKING FAST OVER THE WESTERN HORIZON as Sam Geddis and his younger brother Tully made their way home from Cave Beach through the hills north of Benicia. Sam was leading the way with long strides that made Tully cry out, “Wait for me!”

Sam turned and looked back down the slope. At nine, Sam was tall for his age, with long legs and an unusually large head. Sam smiled, pleased to see he was at least thirty yards ahead of his brother. Tully was thin and frail — a pesky five-year-old who constantly whined and complained. Sam scowled, but stopped and waited anyway. “We’re late, Tully,” he warned. “If we don’t hurry up, Momma will burn our supper again.”

Sam knew all too well how easily this could happen. Ever since their father Talcott Geddis had killed himself with a shotgun a year before, their mother Florin had turned to drink. Often, when they came home from playing with their friends after school, the boys had found her so intoxicated with wine that she had fallen asleep and overcooked their evening meal.

When both boys reached the top of the hill, they saw Florin’s 1919 Maxwell Touring Car moving slowly up the winding dirt road from downtown Benicia. Sam waved at her to stop and pick them up. As they climbed into the back seat, Sam noticed several brown paper bags in the front passenger’s seat. “What’s in the bags?” he asked.

“Ah!” Florin said distractedly. “I went to the Farmer’s Market. I found haricots verts for us. Also des baguette fraiche,” she explained, lapsing into the vocabulary of her preferred ancestral French.

Sam leaned forward and peered inside the largest of the paper bags. It was filled with bottles of red wine. Extracting one of these, he held it up and asked sarcastically, “Baguette, Momma?”

“Ah — that too,” she replied with a vague smile. “Some very fine vin du pays.”

Sam flopped back into his seat, giving his brother a disgusted look. Tully only looked puzzled.

As they rounded the last bend in the road, the Geddis’ house came into view — a large, two-story stucco and wood-frame structure with a mansard roof and six bay windows. Though impressive in size, the house was a grotesque mix of French Provençal and Queen Anne architectural styles. It had been built three years before, when Talcott Geddis had moved his family to Benicia from southern California, where he had been an engineering consultant for several independent oil-drilling firms.

After visiting Benicia on business several times in the past, Talcott had decided Suisun Bay would be the perfect location for an oil refinery. The deep-water channel of the Carquinez Strait offered ready access for seagoing tanker ships coming from the Golden Gate through San Pablo Bay. Such a refinery’s close proximity to the Benicia Arsenal and the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in nearby Vallejo ensured a reliable and growing market for its products. Talcott also knew the increasing slaughter of British and French troops on the Western Front made it likely the United States would soon enter the war against Germany; accordingly, in early March of 1917, he purchased seventy-five acres of land on the western shore of Suisun Bay as the site for his new refinery. This venture proved tremendously successful because of the enormous demand for oil and gasoline that followed America’s declaration of war against Germany.

As many local residents said, Talcott Geddis had “the Midas touch.” When he shot himself just as his new venture began generating millions of dollars, therefore, it was a great mystery to everyone — everyone, that is, except Sam, who knew his mother was contemptuous of her husband.

Sam did not understand exactly why. After all, his father had always seemed reticent and passive — always eager to satisfy Florin’s extravagant demands and tolerant of her frequently dark moods. During the years following the family’s move to Benicia, Florin had berated her husband mercilessly whenever he was home — especially late in the evening, after the boys had gone to bed. All the way from his third-floor bedroom, Sam could hear her shouting and slamming around in the kitchen.

Early one morning, just a few days before Talcott shot himself, Sam had come downstairs to find the man on his knees in the kitchen, whimpering softly as he picked up pieces of broken china and glass scattered on the kitchen floor. When Sam asked what had happened, the oil tycoon could only shake his head in speechless despair.

Talcott had met Florin on his first business trip to Benicia in the spring of 1910. She was working as a housekeeper at the Palace Hotel. Her long brown hair, smooth olive complexion, sensuous lips and flashing eyes had captivated Talcott immediately. Having been raised in the cloistered, all-white world of a wealthy San Luis Obispo family and educated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Talcott knew little about women — least of all exotic working-class women like Florin.

Florin was the granddaughter of a French-Canadian fur trader named Jacques Delong, who had come to the Carquinez Strait in the early 1840s to hunt beaver, which at that time were plentiful in the tule marshes of Suisun Bay. Her maternal grandmother had been a member of the warlike Suisunes tribe and her mother, the “half-breed” wife of a Portuguese sailor.

Abandoned by her mother as an infant, Florin was taken in by the Dominican Sisters of Saint Catherine’s Seminary in Benicia. The nuns did their best to indoctrinate Florin in the ways of the Holy Mother Church. From her ancestors, though, Florin had inherited a fierce independence. When she turned sixteen, therefore, the nuns released her from their care and helped her find employment at the Palace.

Fascinated by this handsome, defiant young woman, Talcott had lured her to his hotel room bed. When he returned to Benicia a few months later and Florin told him she was pregnant, his carefully cultivated sense of noblesse oblige induced him to marry her.

As Florin and her sons turned into the long driveway now, the many tall windows at the front of the Geddis house blazed with the blood-red light of the sunset. “Look!” Florin suddenly declared, pointing at the house. “Papa is home!”

Sam shuddered. “Momma!” he shouted. “Papa’s dead!”

“No-no!” she retorted excitedly. “Don’t you see? He has left the lights on for us.”

Terrified, Sam waited in silence while his mother stopped the car in the driveway, got out and headed for the front entrance carrying only her large bag of wine bottles. “Apport les provisions!” she commanded.

Before the boys entered the kitchen, Florin had already lighted a Turkish cigarette, uncorked one of her new bottles, and poured herself a large glass of Cabernet. While Sam emptied the grocery bags, Florin carried her glass into the front parlor and cranked up her Victrola.

Placing a record on its turntable, she sat down to smoke and sip her wine. Her eyes closed, she serenely slipped into the meandering piano rhapsody of Debussy’s “Claire de Lune.”

1919: Episode 9

SAM WATCHED FLORIN WARILY as he stored the various packages of vegetables, meat, and cheese in the icebox. He felt somewhat less fearful now because his mother was behaving as she usually did — attending to her own wants first and indifferent to what was happening around her. Sam decided if he and his brother were going to get any supper that night he would have to prepare it himself.

Rummaging through the icebox, he found a quart glass jar filled with onion soup his mother had prepared two nights before. Removing this and a block of goat cheese wrapped in brown paper, he placed the items on the kitchen table. Then, loading several pieces of pine kindling into the kitchen stove, he ignited a fire.

By this time, the Debussy piece Florin had been listening to had concluded. Roused from her reverie by the noises in her kitchen, Florin came out to investigate. “Quest-ce que tu fais?” she inquired sweetly.

“Preparing supper,” Sam replied. “It’s time, Momma. Tully and I are hungry.”

“Mai sure! Pardon moi, mes chers!” Florin gushed. Then, noticing the cheese and soup jar on the kitchen table, she said, “Ah non! Pas le potage! I make crepes suzette, nest-ce-pas?” Opening the icebox, she extracted one of her newest purchases. “And look — I buy saucisse for you!”

Annoyed that his mother poured herself yet another glass of wine before she placed the iron skillet on the stove, Sam was satisfied he had sufficiently reminded Florin of her maternal duties. He therefore challenged Tully to a game of jacks on the kitchen floor, directly in front of the stove.

“Pas ici!” Florin said sharply as she dropped the sausages into her skillet.

Shrugging defiance, Sam picked up his jacks and moved them to another part of the room, where his superior skill quickly reduced his brother to tears.

“Sammy,” Florin urged. “Be gentle, mon cher.”

“But he’s such a crybaby!” Sam protested.

“Perhaps you should both wash your hands now,” Florin suggested softly. “Supper will be ready soon.”

“I hope so!” Sam groused as he marched to the kitchen sink, splashed cold water over his soiled hands, and wiped them on a dish towel.

Florin’s eyes flickered with anger. Grabbing the towel from Sam, she snarled, “Your trousers and shoes are covered with mud! Go upstairs and change! Vite! Vite!”

Sam ignored this directive and continued playing his game of jacks. Frustrated by Sam’s defiance, Florin retaliated as she always did — by showering affection on her youngest. “Tee-Tee,” she murmured solicitously, using the nickname she had assigned to Tully when he was born. “Come wash your hands, mon petit.”

Tully promptly obeyed, smiling blissfully up at his mother as she took a bar of soap and carefully washed his and her own hands together in a pan of warm water. Then, taking a clean hand-towel from a cabinet drawer, she dried first her son’s and then her own hands. Kissing him lightly on the forehead, she warbled, “T’asseoit, mon petit.”

Sam had already taken his place at the head of the kitchen table where his father had customarily sat and was now tapping on the tabletop with a fork, impatient for his mother to serve him.

Carefully rolling the crepe on their plates and sprinkling them with powdered sugar, Florin added the crisply sautéed sausages and, spreading wide her arms in a dramatic gesture, declared, “Voila!”

Tully applauded vigorously, but Sam continued rapping his fork on the tabletop. Florin signaled her displeasure with this by serving Tully first. Then, as they began eating, she poured each of them a glass of milk and herself another glass of wine.

She did not sit down with them at the table, preferring to stand at the sink and watch them while she sipped her wine. It was just as she had done when his father was alive, Sam remembered. Since Talcott often returned home late from work, Florin would wait to dine and, usually, rebuke him for his tardiness.

The boys devoured their food in silence for several minutes. Satisfied that she had done her duty, Florin returned to the front parlor and put another record on her Victrola — this time a series of lively ballads sung in French by a man accompanying himself on guitar.

As the music drifted into the kitchen, Florin returned carrying a newspaper and her glass of wine. This time, she sat down at the table and began reading. “Ecoutez!” she suddenly declared and read aloud a headline on the front page: “‘First Daytime Mail Flight from San Francisco to New York in 33 hours.’”

Florin spread the opened newspaper out on the table and pointed to the photograph of a smiling aviator standing in front of a single-engine bi-plane. The caption read: “Veteran aviator James H. ‘Jack’ Knight stands beside his Havilland DH-4.”

Sam moved to get a closer look. His mother leaned over his shoulder and read aloud the first paragraph of the news story.

“Let me read it,” Sam insisted, snatching up the paper. He started perusing the news report with both his index fingers.

“Can I see?” Tully asked, running around the table. Sam pushed him away. “Get out of here! You can’t read.”

“Come, Tee-Tee,” Florin said, taking Tully’s hand and coaxing him to follow her back into the front parlor.

Much later that evening, long after Sam had gone up to his room to work on a model plane he was building, Florin awoke from her wine-induced doze. Rising slowly from her chair, she stood unsteadily for several seconds, looking around the room until she noticed Tully sound asleep on the sofa. Stepping softly toward him, she touched his shoulder and whispered, “Come, Tee-Tee. It is time for bed.”

The boy flinched slightly at her touch. Then, without opening his eyes, he sat up and put out his arms to be carried. Though Tully was small for his age, Florin was not at all sure that in her inebriated condition she was ready to carry him. “No, Tee-Tee. If you want to sleep with Momma, you must walk upstairs yourself.”

Reluctantly, the boy stood up and allowed his mother to take him by the hand into the front foyer and up the staircase to her room. After removing Tully’s clothes, Florin gently helped him climb into her bed. Removing her own clothes, she climbed in beside him.

1919: Episode 10

JACK HAD BEEN LATE FOR SUPPER, and his clothing was covered with mud. “Where have you been to get so dirty?” Gail demanded.

“Just out playin’,” he said as he flounced into her mohair armchair and noisily bit into an apple he had taken from the fruit bowl on the kitchen counter.

Gail snatched the apple from his hand. “Don’t eat that now!” she scolded. “It’s supper time. Go clean yourself up and get out of those filthy clothes!”

Angrily, Jack bounced up out of the armchair and marched into the bathroom, slamming the door behind him. He emerged minutes later wearing nothing but his undershirt and boxer shorts. Again, he flounced into the armchair.

“What’s wrong with you, Jack? I told you to change your clothes, not strip down to your skivvies!”

“What do you care?” he asked sullenly.

Gail began to worry. This defiant behavior was not at all typical of her son, who was usually a good boy, obedient and kind to his mother. Her voice softening, she walked over to him and touched his forehead. “Are you sick, dear?”

“No. I ain’t sick!” he retorted, pulling away from her.

“I am not sick,” she corrected.

“Dammit!” Jack shouted and leaped to his feet. “You’re always correcting me! You’re worse than Del!”

“How dare you swear like that!” Gail shouted back. “I’ll wash your mouth out with soap, you fresh thing!” Swiftly, she moved toward the sink to carry out her threat.

This was enough to give Jack pause. Hanging his head, “Sorry,” he mumbled, still resentful. “I’m sick of people always picking on me for my grammar.”

“We’re not talking about grammar, mister!” Gail warned. “I’m raising you to be a gentleman, and gentlemen don’t talk that way to ladies — least of all their own mothers!”

Jack glared at her.

Gail stood with her hands on her hips, studying her son in silence for several seconds. At last, she said, “Go put on a clean shirt and trousers. Gentlemen don’t go strutting around half-naked in front of ladies either.”

Jack eyed his mother suspiciously. “Oh no? Then, why does Soames take off his collar and tie when he’s here?”

This retort rocked Gail back on her heels. “That’s not fair, Jack! It was very hot when he was here Saturday. Mister Soames was our guest. I suggested he remove his collar and tie so he’d be more comfortable.”

“Seems like he’s getting a little too comfortable, if you ask me,” Jack groused.

Instinctively, Gail cocked her right arm, barely managing to refrain from slapping her son in the face. “Nobody asked you,” she said coldly. “Now, go get dressed!”

Jack did what his mother had asked and changed into clean clothes. But the two of them ate supper in silence. As soon as he finished eating, Jack got up from the table and started toward his bedroom.

“You didn’t excuse yourself, Jack,” his mother said.

Jack ignored this reproof and entered his bedroom, closing the door behind him.

Gail remained seated at the table in silence for several seconds, not sure what she should do. At length, she stood up and cleared the table. Stacking the dirty dishes in the kitchen sink, she sat down in her armchair to read the newspaper, determined to distract herself from the turmoil she was feeling.

After the sun went down, she opened the cupboard over her kitchen sink, reached up on the top shelf, and took out the bottle of sherry Soames had brought her as a gift from San Francisco. She filled a teacup with the sweet-smelling wine and sipped it slowly, hoping it would help her sleep. But one teacup was not enough, so she had another. And then another.

Even this did not help. For, after she went to bed at ten o’clock, she lay wide-eyed with worry, keenly aware of the nocturnal clanking and hooting railroad noises she had long since grown accustomed to.

Was her son also unable to sleep? She wanted to get up and go to him, take him in her arms and hold him as she had when he was a little boy — assure him that everything was all right.

But she knew it was not. “Nothing will ever be all right again,” she whispered to herself in the dark, tasting the bitter salt of her own tears.

1919: Episode 11

“GOOD MORNING GAIL!” IRA JACOBS CHIRRUPED as Gail entered Ahern’s Import/Export building. “Ready for another exciting day at the office?” he added with a wink.

“Awfully sorry I’m late, Ira,” Gail replied. “I had kind of a bad night last night. Couldn’t get to sleep for some reason.” She had entered just as the big Monitor clock on the office wall was chiming 8 a.m.

Ira, Ahern’s local branch manager, was a short, chubby man in his late forties. His receding hairline, bulging brown eyes, and wide mouth down-turned at the corners reminded Gail of a perpetually sad frog. “Don’t worry, Gail,” Ira smiled as best as he could. “You’re not late. Look at the clock. It wouldn’t matter anyway, my dear. You’re so fast and efficient, you could come in at noon and still do all the work you need to do.”

Ira had a heart-aching crush on this handsome woman. At five feet, eight inches tall with a long, graceful neck and torso as well as an ample bosom, Gail was what women of her mother’s generation called a “statuesque beauty.” Though seemingly reserved and even-tempered, Gail simmered with latent sensuality. She was very much like her mother in this respect. But, in her ability to concentrate for long hours on performing repetitive arithmetic tasks, she was very like her father.

Ira had been infatuated with this woman ever since she first walked into the office two years before, seeking work as a totally inexperienced clerk. His instantaneous assessment of her bookkeeping skills had been unemotional — keen and accurate. In less than two weeks, Gail Westlake mastered all the subtleties of posting and balancing the scores of customer accounts the office handled every day.

“You’re too kind, Ira,” Gail said as she sat down at her desk and promptly began sorting through the stack of order forms piled there. Shuffling through these in a preliminary inspection, she asked, “Did Mister Grimes drop off those new shipping schedules you wanted yet?”

Ira threw both his arms up over his head and rolled his eyes in exasperation. “Who’s to know with that guy! They were supposed to be ready last week. Tell you what — I’m gonna call him right now. This is making me crazy!”

Ira picked up the candle phone on his desk. “Alice, get me 6324-R2,” he barked into the receiver. “And please do not eavesdrop!” he added irritably. “This call is none of your business!” Thrumming his fingers on his desk blotter, Ira waited impatiently for the right party to answer.

“Grimes — is that you? Where’s my shipping schedules? … What d’ y’ mean they ain’t ready yet? It’s been two weeks since we ordered ’em, already!” There was a long pause during which Grimes was apparently trying to explain the delay. “Don’t gimme that!” Ira made a face at Gail, who was now totally engrossed in her work. “You got a problem with your printing press? So what am I supposed to do about it? I got customers to take care of here. They won’t wait.” Another pause, longer this time. “Tomorrow’s not good enough!” Ira snarled. “I got t’ have ’em today!” Hanging up the phone, Ira again threw up his arms in exasperation and scowled at Gail. “He says he’ll drop ’em off this afternoon. He better!”

Accustomed to Ira’s irritability, Gail had long since learned to ignore it. She knew it would never be directed against her. She also knew Ira Jacob’s bark was bigger than his bite. The man was a showman. He would have been much happier and more effective, she thought, in vaudeville.

Suddenly the street door opened, admitting a frail, wispy-haired woman with a face like a hatchet and the quick, furtive movements of a ferret. It was Gail’s friend, Snooky Wells. Though only thirty-eight, Snooky looked like an old woman — stoop-shouldered, her face heavily creased with wrinkles and her hands mottled with brown spots.

“Hey, lady,” Snooky rasped at Gail in her hoarse barfly voice. Snooky was both a heavy drinker and an inveterate smoker. She puffed whenever she could. It didn’t matter whether it was one of her many boyfriends’ cheap cigars or her own corncob pipe: Snooky thrived in a constant cloud of smoke. “How y’ doin’, Ira?” she said to Gail’s boss.

“I’m good,” Ira replied amicably but warily. He was amused by this eccentric creature and, because she was Gail’s friend, he tolerated her always-bizarre behavior and questionable morals. “How’s Alfie these days?” he asked, peering through the big street-front window at the small figure huddled in a wooden wheelchair outside. Alfie was Snooky’s quadriplegic seven-year-old son.

“Alfie’s great! Would you believe it? That kid never gets sick!” Snooky eyeballed Gail mischievously.

Gail knew her friend regarded her hopelessly crippled and dependent son as God’s punishment for her own sins. Snooky had been raised a Roman Catholic. Despite her always irreverent views of Church traditions and her defiant persistence in violating its most fundamental moral precepts, Snooky was ruthlessly honest with herself. “I’m a scarlet woman,” Snooky had often confessed to Gail. “Ain’t no doubt about it, an’ I’ll prob’ly fry in Hell for it. But — you know what? That little sucker out there could be my ticket to Heaven, so I’m gonna do whatever I gotta do to keep him happy an’ healthy!”

Snooky had been faithful to that vow. Though few Benicia residents approved of Snooky’s ways, practically everyone commiserated with her plight. Soon after Alfie had been born, Snooky’s husband, Zeke Wells — a notorious town drunk and one-time crony of Jack London — had quit his job at McClaren’s Tannery and jumped a freight car to travel nobody knew where. Furious and destitute, Snooky used the only talents she had to support herself and her son.

Ever since she was six years old, Snooky had played the five-string banjo — the only family heirloom passed down to her from her paternal grandmother, who in 1846 had migrated with her family from Minnesota to California in a Conestoga wagon. By the time she was sixteen, Snooky could frail like Earl Scruggs and wail like Libby Holman. With the survival instincts she had inherited from her pioneering ancestors, it was only natural for Snooky to seek employment as an entertainer in Benicia’s many waterfront saloons.

Patrons of these establishments loved her, and proprietors rewarded her with nightly engagements where customer tips helped pay her rent and put food on her table. Alfie was always a part of these entertainments, posted front and center in his wheelchair wherever Snooky performed. While she would belt out her raucous “torch” songs or lead her audience in sing-alongs, Alfie collected the coins customers dropped in the tin can on his lap. “We got no shame!” Snooky proudly declared.

Gail stood up and rushed to embrace her friend, signaling with a quick glance at Ira her wish to share confidences with Snooky. Ira nodded his approval and the two women went outside, where Gail gave Alfie a greeting hug. He responded with a drooling smile and his own garbled greeting, “Hewo, Pail. I wove you.” Gail’s eyes instantly filled with tears. “I love you too, dearest boy!”

Extracting a corncob pipe and a box of matches from the gunnysack she always carried as a purse, Snooky lit up. Speaking through clenched teeth, she asked, “So how’s old Soames these days?”

“Don’t ask,” Gail said grimly. “I think Jack knows about us. It’s not good.”

Snooky leered at her friend through a thick cloud of pipe smoke. “Don’t worry about it. He was bound to find out sometime. You think boys his age don’t already know ’bout that stuff?” Then, laughing harshly, she added, “In this town?”

Gail shook her head. “You may be right. Still – it’s not good.”

“It’s all part o’ growin’ up, honey. Better he learns ’bout it from you than one o’ them damn whores down there.” Snooky nodded in the direction of the waterfront where they now heard the loud hooting of a train whistle. “You goin’ to the parade Sunday?” Snooky asked, realizing it was time to change the subject.

Gail was still looking toward the waterfront, preoccupied with her own anxious thoughts. Finally, she said, “I suppose so. I understand it’s going to be a big event.”