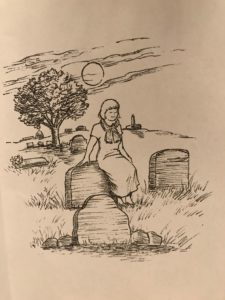

In this sketch, Elsie Robinson makes a pact with God in the Benicia Cemtery for an exciting life. (Sketch by Angela Hanlon)

Twenty million daily readers.

Two thousand fan letters a day.

Four full-time personal secretaries.

A real-life Brenda Starr-type reporter, but also a beloved advice columnist before Ann Landers and Dear Abby—meet former Benician and nationally-known syndicated Hearst columnist, Elsie Robinson.

A sample of her work:

“Stop a minute, World.

“Every day they come in, those jealously letters…you know the rest, World…always after the first paragraph they bite the atmosphere. And they always end up asking what I’d advise.”

“I believe in flying in a temper and beating up the neighborhood—if it gets you anywhere. I believe in weeping and hagging and scolding and sniffing and following him through the streets—if you get the results you’re after. But do you? No, you don’t Sister or Brother, and no one else ever did.”

“The plain truth is that you don’t own that other person—nope, not even if you’ve been married fifty years.”

What another person does is his or her own affair, not yours. “It may hurt a plenty—you may feel it will smash life for you. But you haven’t any business to let it smash your life. YOUR OWN HAPPINESS is your business.”

And the above is simply part of Elsie’s advice on jealousy, in one newspaper column, published in March of 1920.

Probably most of you reading this have never heard of Elsie. Yet, if you are a Benician, you are living and/or working in the town where she was born and raised—just above Military on West 2nd Street, on the plot of land where the Congregational Church is now, on the road that once led to the entrance of the City Cemetery.

“Good evening, Friends—A man I know found a nickel the other day. It was a great occasion for him and he really deserved it. All his life he had been preparing for that find by going about with his head down, scanning the cracks and dark places.”

“To be sure it was a habit that had inconveniences. Rainbows and sunshine shimmered in the sky—but he never saw them…Foam drifts of blossoms in the spring—leaf fires in the fall—the evening star—the webs of silver rain—all came and passed; he did not know.”

“The faces of all human things went by along his road; men with their eyes filled with adventures and war; women alight with dreams and love and little, laughing…children on tip-toe with excitement and curiosity all bubbling over with the rush and joy of life.”

“He did not see them…He only saw the cracks and seams and hidden places in the mud where the FIND might lurk. And so—

“He found a nickel. LUCKY—wasn’t he?”

Elsie probably encountered more than one nickel-hunter here during her Benicia youth. Other gentlemen of Elsie’s Benicia acquaintance inspired this:

“I’ll just bet you anything that when some of those pious old boys that made my early years miserable crawl out on the judgment day and drop around to the check room to get their souls, they’ll get something handed to them that looks like a DRIED-UP POLLYWOG. I betchu.”

By now, you have probably gathered: Elsie said what she felt, what she thought people needed to hear, what she wanted to say—no holds barred. At the same time, she recognized that she could make some people feel uncomfortable. For example, she opened her “Pollywog” column with these words:

“I certainly am getting in wrong with this here column. Ever since I stopped limiting myself to a discussion of gingham curtains and began giving the Established Order of Things a few feeble digs in the ribs, there’s been hellsapoppin.”

But even after noting that her mother (“who’s a lady in spite of what she created”) wouldn’t allow the subject of Elsie’s columns to be mentioned in her presence…and her editor “snarls”–“I told you to write a CHEER-UP COLUMN—not a BUST-UP one!’” she “felt another surge coming on and “I’ve got to give vent to it even if it lands me in the isolation ward of the county hospital.”

Elsie would go on venting, first with the Oakland Tribune, later as a columnist and reporter for the Hearst newspapers, for more than 35 years. At the height of her popularity the column was entitled “Listen, World!” This title and column became so well-known that at least one advertiser, probably without Elsie’s permission, linked itsself with her by using the phrase to announce an ad for chocolate milk.

In 1934 she published a memoir, “I Wanted Out!” As described by Kirkus Review:

“A human interest document, first and foremost, written with breezy, colloquial vigor and spontaneity. And second, the life story of one who is known to readers of Hearst newspapers the country over for her syndicated column over the signature ‘Aunt Elsie.’ A story of courage. A story of struggle against insuperable odds. A story of inner conflict, of unpreparedness for life, of an unquenchable determination to get out of life what there was in it, for herself and for the boy she had born. A childhood in a small California town — a girl marriage, crashing on the rocks of New England austerity — a struggle against direst poverty, first as a miner where she learned to know the value of companionship with men, then breaking into the field of journalism. She knows people. And people will like this.”

You can read I Wanted Out! thanks to the generosity of Benician Steve McKee. His gift of three copies of Elsie’s books are available for check out at the Benicia Library.

For even more on Elsie check out McKee’s recent, excellent, column in the Benicia Herald:

If you’d like to meet Elsie, lucky for us she’ll be returning to Benicia on Sunday, Sept. 17 at 1 p.m. Oh, and her husband Benton Fremont—grandson of John C. Fremont, the great explorer and one of California’s first U.S. senators—will be here as well. They’ll be stopping by the building she remembers as City Hall, the Benicia State Capitol.

Come, stop by and say “Hi.”

Leave a Reply