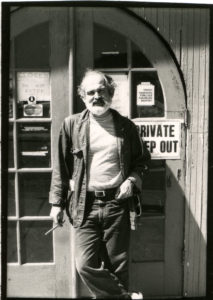

A 1971 photograph of Robert Arneson outside his studio at 146 West E St. (Copyright 2017 Estate of Robert Arneson.)

Arts Benicia is celebrating its 30th anniversary throughout 2017. What does it take for a non-profit arts association to survive and thrive over a 30-year period? It takes commitment, the support of a community, luck, funding, and most of all, dedicated people who simply will not let it fail. Over the course of the year, we will explore all of these elements as we look at the founding of Arts Benicia, its long history, its importance to our community and the region, and most of all, the people who have been central to the organization through the years.

1970s Benicia: An Artists’ Haven

Although Arts Benicia was not formally organized until 1987, there was already a strong community of artists in place. They had discovered Benicia in the 1960s and 1970s, finding a tucked-away town that seemed just the place to live and work creatively.

First, there was plenty of space, and that space was cheap. In 1963, the U.S. Army had de-activated the Benicia Arsenal which had been part of the town’s landscape on Suisun Bay for more than 100 years. The Yuba Manufacturing Company, also on Benicia’s eastern waterfront, had closed its plant in 1972. Between those two empty complexes, artists could find large, open spaces to work at very reasonable rents in the empty buildings and warehouses.

“We moved into the Yuba Building in 1974,” said glassmaker Ann Corcoran, who founded Nourot Glass with her partner and husband Micheal Nourot. “It was perfect for us. Steve Smyers was already there, Joe Morel would come soon after. We had all this great, open, run-down space, ideal for a group of young glass artists to work.”

Artists also found the town to be conveniently located to the many colleges, universities and art schools in the corridor stretching from San Francisco to Davis and on to Sacramento where many Benicia artists worked as instructors. In the 1960s, UC Davis was establishing its new Department of Art. Founding chair Richard L. Nelson had gathered some of the country’s most influential and cutting-edge contemporary artists as instructors. A metal Quonset hut called TB-9 served as both classroom and studio.

They came to be known as the Dream Team, a group of the most innovative and fearless artists ever gathered in a university setting. These artists and teachers—Robert Arneson, Manuel Neri, Wayne Thiebaud, William T. Wiley, Roy De Forest, and others— would change the way the West Coast and America would look at art, as social and political commentary on the times. Of the Dream Team members, both Arneson and Neri had ties to Benicia and would encourage others to move to the small town on the Strait.

Then there were the intangible elements: some artists say that it was the light that attracted them to Benicia, the way the sun arcs across the Strait before falling into the bay beyond the Carquinez Bridge.

“There is this amazing painter’s light here,” said Pam Dixon, a long-time Benicia artist. “The Strait is very different from the ocean; more intimate. It creates a moody, melancholic, and yet uplifting atmosphere. That’s why this town is loaded with plein air painters.”

Others say it was the industrial decay and rust of the nearly falling-down buildings in town and the warehouses on the waterfront that appealed to them.

“In the 1960s and ’70s, Benicia looked like industry was still here, even though most had pulled out,” Dixon said. “It hadn’t been tricked out at all. There wasn’t the money to pull the buildings down, so it still looked like it had in the ’30s and ’40s, rusting and decaying. As artists, we loved it.”

Two critically important artists came because it was home. Glassmakers Nourot and Corcoran came to Benicia because Nourot’s grandfather had lived here, and he knew the town well. Ceramic sculptor Arneson came because he was born and grew up in Benicia, playing football at Benicia High and drawing cartoons for the Benicia Herald as a teen.

Nourot, a native of Fairfield, had honed his craft as one of the 16 original students at the famous Pilchuck Glass School in Stanwood, Washington. By 1973, he had returned from studying and working in Murano, Italy and had opened his first studio, Light Opera, in San Francisco. He had met his future wife and fellow glassmaker, Ann Corcoran, who worked with him at Light Opera. Together, they wanted a larger space where they could build the kind of furnace they dreamed of.

At the same time, Arneson was a professor of art at UC Davis, married to fellow artist Sandra Shannonhouse, and raising his four sons from his first marriage. He was also well on his way to establishing a reputation as an important ceramic sculptor, a leader in contemporary art, and one of the leaders of California Funk, considered one of the state’s most original art movements.

“He was one of the first to make the art world see ceramics as a fine art form instead of just the production of pots,” Shannonhouse said. “His work was playful, colorful, irreverent, and taken very seriously, sparking political and social commentary, by galleries, museums and collectors across the country.”

Yet Benicia native son Bob Arneson was still missing something, a place to work quietly and privately, away from the hustling beehive of TB-9. It was time to go home.

1970s Benicia: An Artists’ Haven: Part II can be viewed here.

Vicki… a wonderful piece on Benicia, I keep hoping that someone will pick up the gauntlet and write a book about the artistic history of Benicia. Now, when a few of our important Artists are still living. I can hardly wait for the second chapter of your fabulous article.