A SOFT-STORY BUILDING has inadequate bracing on the first-floor front wall, often because of a large glass storefront. When the mass of this building gets to swaying, the structure is at serious risk of collapse.

Steve McKee photos

Editor’s note: Last of two parts. Read the first part by CLICKING HERE.

A FEW WEEKS AFTER THE RECENT NAPA EARTHQUAKE, builder John Laverty told me he had seen several of the Napa projects we had done together and that they held up great in the shaking. That was good to hear. Year after year, we work to design and build extra strength into these houses by calling for extra plywood nailed tight to strengthen walls and metal straps nailed off to bridge any framing joints that undergo major tension during a shake. We do all of this, house after house, for that singular moment that we know will randomly show up one of these decades when 15 or 20 seconds of violence test our houses. It was heartening to have observable proof that our efforts are paying off. These days we really do know how to make a house safer from earthquakes.

A FEW WEEKS AFTER THE RECENT NAPA EARTHQUAKE, builder John Laverty told me he had seen several of the Napa projects we had done together and that they held up great in the shaking. That was good to hear. Year after year, we work to design and build extra strength into these houses by calling for extra plywood nailed tight to strengthen walls and metal straps nailed off to bridge any framing joints that undergo major tension during a shake. We do all of this, house after house, for that singular moment that we know will randomly show up one of these decades when 15 or 20 seconds of violence test our houses. It was heartening to have observable proof that our efforts are paying off. These days we really do know how to make a house safer from earthquakes.

Meanwhile, texts and photos continued to arrive from Phil Joy showing older houses that needed to be hoisted by his house lifting crew for major repair work. Often there was some key weakness that could have been remedied for a few thousand dollars. I imagine that those owners would surely love a chance to go back in time and make those retrofits.

Here is what I learned from the recent Napa earthquake.

Don’t assume past performance is an indication of earthquake readiness

It seems logical that if your house or building has a history of surviving past earthquakes (such as the 1906 San Francisco and the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquakes) that it’s proven to have certain strength that will help it survive future quakes. In the absence of X-ray vision to examine hidden structural components, I’ve fallen into that way of thinking myself. No more — not after seeing the crumpled corners and fallen brick parapets of Napa and Vallejo buildings that had survived those previous earthquakes without damage.

Beware seemingly inactive local fault lines

In Benicia, our local fault line is the Concord-Green Valley Fault. The last large earthquake occurred there between 200 and 500 years ago, says the U.S. Geological Survey. It’s not nearly as noteworthy as the famous San Andreas Fault or the sort-of-famous Hayward Fault. It seems to be so small and inactive that it’s not worthy of our concern. But then that’s what people thought of the West Napa Fault until 3:20 a.m. on a recent August morning.

Distinguish real preparedness steps from the lists mentioned by the talking haircuts on TV

Yes, yes, have a spare flashlight and some spare water stored somewhere. Now can we talk about real preparedness?

Strapping your water heater is a good start. Then get help to determine if any of your building components are at risk. A structural engineer or an architect versed in these concepts can help with this.

Reinforce the cripple walls!

If I could list just one thing, this would be it. It’s one of the easiest and most effective upgrades you can do. Only certain houses need it. But they really need it.

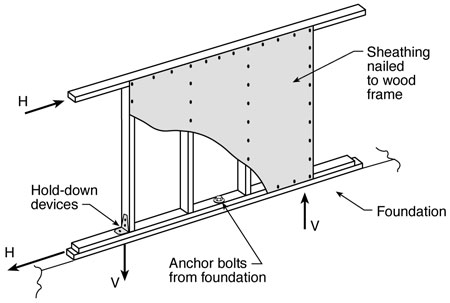

Some houses have wood-frame floors that are raised up a couple feet or more above the concrete foundation by sitting on short wood-frame walls. These “cripple walls” are often the weak point in earthquakes because they’re not up to the task of resisting the sideways force as the huge weight of the house rocks back and forth. A two-story house with cripple walls below is even more at risk because of the extra weight.

Solution: Connect the wood framing at the bottom of the cripple wall to the foundation with 5/8-inch bolts (or add special metal connectors called “universal foundation plates” that can get installed sideways if working clearance is limited). Also, connect the top of the cripple wall to the floor framing with nail-on metal connectors (either the “A35” or the “H10” clip as shown in the Simpson Strong-tie catalogue, the industry standard and available online). Then add half-inch-thick plywood that spans from top to bottom of this wood framing and is well nailed, with a nail every 4 or 6 inches. Cover 16 feet of all outside cripple walls with this and you’ll be in much better shape to ride out the next temblor. See the diagram at left.

Solution: Connect the wood framing at the bottom of the cripple wall to the foundation with 5/8-inch bolts (or add special metal connectors called “universal foundation plates” that can get installed sideways if working clearance is limited). Also, connect the top of the cripple wall to the floor framing with nail-on metal connectors (either the “A35” or the “H10” clip as shown in the Simpson Strong-tie catalogue, the industry standard and available online). Then add half-inch-thick plywood that spans from top to bottom of this wood framing and is well nailed, with a nail every 4 or 6 inches. Cover 16 feet of all outside cripple walls with this and you’ll be in much better shape to ride out the next temblor. See the diagram at left.

Tall brick chimneys are just waiting to snap

The old chimneys in downtown houses in Benicia are particularly at risk, especially the taller ones. Check to see if the mortar has grown so weak that the chimney should be removed. The least you can do is add a metal pole brace at an angle from the roof to a steel band wrapping the chimney up high. Preferably two such braces that angle away from each other back onto the roof to “triangulate” the chimney and add rigidity in all directions.

Reinforcing the cripple walls will keep the house from rocking as much and will give brick fireplaces and chimneys a fighting chance of surviving. (See what I mean about how important it is to have strong cripple walls?)

Earthquake reinforcements are a better value than earthquake insurance

Earthquake insurance can cost a thousand dollars per year and often much more. Insurance companies raised their rates after the Northridge earthquake in 1994 when their industry got hit with a big bill. The deductibles are high — 10 and 15 percent. That means the homeowner has to pay the first $40,000 or $60,000 or $80,000 of repairs themselves before insurance money starts to help! I’d rather pay the one-time cost of earthquake strengthening and forego paying the yearly earthquake insurance premium. But that’s just me.

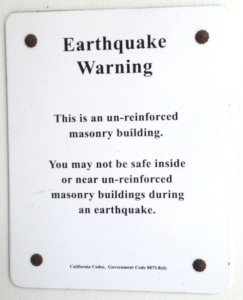

ALL OLD BUILDINGS have disclaimers like this one. Some cities are more rigorous than Benicia in requiring owners to reinforce their buildings.

If you live in a house built in the last 30 years or so, your house was built in the era of modern earthquake engineering. Good for you. You have shear walls embedded here and there in your house walls and reasonably good metal connections to your foundation. You should do well in future earthquakes. Some of you may have a potential weak spot if you have a second-story room over a garage. The end wall of the garage that is mostly just a big opening for the door is probably the weakest point of your house for earthquake resistance. Plywood and foundation bolts added to these narrow walls (on the inside face, because that’s easier than disturbing the siding and trim on the outside face) will help you avoid major damage.

Houses downtown built before the fifties have special needs

Houses constructed before the Second World War are from an age when designers and builders were especially clueless about how to defend against earthquake damage. These houses may have unreinforced cripple walls or insufficient bolts attaching the wood framing to the foundation, as discussed above.

Old First Street buildings with large glass storefronts are the biggest risks of all

So many of the older downtown buildings are big, heavy, two-story structures. There’s usually a nice, strong, boxy building on the top and an open floor plan below that includes large areas of glass on the street front.

These buildings have what is called a “soft story” and desperately need to have a steel “moment-resisting” frame added just inside the front wall. This new frame will be hidden as much as possible and run along the top and corners of the front wall. A strong concrete foundation will be added at the two ends of the frame to anchor this frame (and thereby the building) rigidly to the Earth.

The $20,000 (or so) to do this retrofitting will seem like a bargain compared to losing the building (or worse!).

* * *

EVEN AFTER EVERYTHING I JUST WROTE, I think it’s mostly good news. There a few key spots in our buildings where we need to pay attention, and we know what they are. We understand what we need to do and have only ourselves to blame for inaction.

Steve McKee is a Benicia architect specializing in residential design. He can be reached on the Web at www.smckee.com or at 707-746-6788.

Leave a Reply